Which Of The Following Is Not A Nucleophile Chegg

Holbox

Mar 15, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

Which of the Following is NOT a Nucleophile? A Deep Dive into Nucleophilic Chemistry

Determining which molecule is not a nucleophile requires a solid understanding of nucleophilic behavior. This article delves into the fundamentals of nucleophilicity, explores various factors influencing nucleophilic strength, and provides a comprehensive analysis to definitively answer the question: which of the following is not a nucleophile? We'll dissect different chemical species and explain why some are potent nucleophiles while others aren't.

Understanding Nucleophiles: The Basics

A nucleophile, literally meaning "nucleus-loving," is a chemical species that donates an electron pair to an electrophile (an electron-deficient species) to form a chemical bond. This donation occurs through a process called nucleophilic attack. The defining characteristic of a nucleophile is the presence of a lone pair of electrons or a readily available pi bond. This electron-rich nature allows it to seek out positive or partially positive centers within other molecules.

Factors Affecting Nucleophilicity:

Several factors influence a molecule's nucleophilicity:

-

Charge: Negatively charged species are generally stronger nucleophiles than neutral ones. The extra electron density enhances their ability to donate electrons. For example, OH⁻ is a stronger nucleophile than H₂O.

-

Electronegativity: Less electronegative atoms are better nucleophiles. Electronegative atoms hold onto their electrons tightly, making them less likely to donate them. Therefore, nucleophilicity generally decreases as you move up and to the right on the periodic table (excluding hydrogen).

-

Steric Hindrance: Bulky groups surrounding the nucleophilic atom can hinder its approach to the electrophilic center. This steric hindrance reduces nucleophilicity. A smaller nucleophile can approach the electrophile more easily.

-

Solvent Effects: The solvent plays a crucial role. Protic solvents (solvents with O-H or N-H bonds) can solvate nucleophiles, reducing their reactivity. Aprotic solvents (solvents without O-H or N-H bonds) generally enhance nucleophilicity.

Common Nucleophiles:

Many functional groups and molecules act as nucleophiles. Some of the most common examples include:

-

Hydroxide ion (OH⁻): A strong nucleophile due to its negative charge.

-

Halide ions (F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻): The nucleophilicity increases down the group (I⁻ > Br⁻ > Cl⁻ > F⁻) due to increasing size and decreasing electronegativity.

-

Alkoxide ions (RO⁻): Strong nucleophiles similar to hydroxide ions.

-

Thiolate ions (RS⁻): Stronger nucleophiles than alkoxide ions due to sulfur's larger size and lower electronegativity.

-

Amines (R₃N): Neutral nucleophiles with a lone pair on the nitrogen atom.

-

Water (H₂O): A weak nucleophile, but its abundance makes it relevant in many reactions.

-

Ammonia (NH₃): A weak nucleophile, similar to water.

-

Carbanions (R⁻): Extremely strong nucleophiles due to their negative charge and the presence of a lone pair of electrons on the carbon atom.

Identifying Non-Nucleophiles:

Identifying something as not a nucleophile usually involves the absence of the key characteristic: readily available electron pairs. Molecules lacking lone pairs or readily available pi bonds are generally poor nucleophiles. This often includes:

-

Alkanes (R-H): Alkanes have only C-H sigma bonds, with no readily available electrons for donation.

-

Alkenes (in some cases): While alkenes possess a pi bond, the electron density in the pi bond is often not readily available for nucleophilic attack unless activated by other groups. They are more likely to act as electrophiles, particularly with strong nucleophiles.

-

Alkenes (without activating groups): Unlike alkynes, alkenes are less likely to act as nucleophiles unless activated by electron-donating groups.

-

Certain saturated hydrocarbons: Without an electronegative atom or an available lone pair, these molecules are unlikely to act as nucleophiles.

-

Some highly substituted molecules: Steric hindrance might prevent nucleophilic attack, effectively rendering a molecule a poor nucleophile despite possessing an available lone pair.

Example Scenarios and Analysis:

Let's consider a hypothetical multiple-choice question:

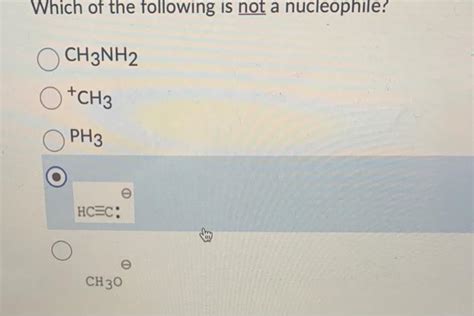

Which of the following is NOT a nucleophile?

a) CH₃O⁻ (Methoxide ion) b) H₂O (Water) c) CH₄ (Methane) d) NH₃ (Ammonia)

Analysis:

-

a) CH₃O⁻ (Methoxide ion): A strong nucleophile due to its negative charge and the lone pairs on the oxygen atom.

-

b) H₂O (Water): A weak nucleophile due to the lone pairs on the oxygen atom, although its nucleophilicity is often less pronounced compared to others on the list.

-

c) CH₄ (Methane): Methane has only C-H sigma bonds, no lone pairs, and is therefore not a nucleophile.

-

d) NH₃ (Ammonia): A weak nucleophile due to the lone pair on the nitrogen atom.

Conclusion: In this example, the correct answer is c) CH₄ (Methane). Methane lacks the necessary lone pair or readily available electrons to act as a nucleophile.

Advanced Considerations: Ambiguous Cases

Some molecules can exhibit nucleophilic behavior under specific conditions. These might include molecules with highly polarized bonds or those possessing pi bonds that can be activated under specific reaction conditions or in the presence of catalysts. The reactivity of such molecules is context-dependent.

Practical Applications and Importance:

Understanding nucleophilicity is crucial in organic chemistry and numerous other fields. Nucleophilic reactions are fundamental to many synthetic processes, including the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, polymers, and other valuable materials. Enzyme activity, a cornerstone of biochemistry, also heavily relies on nucleophilic attack mechanisms.

Further Exploration:

To enhance your understanding of nucleophilicity, consider exploring the following:

- The HSAB (Hard Soft Acid Base) theory: This theory helps predict the reactivity of nucleophiles and electrophiles based on their hardness and softness.

- Leaving group effects: The nature of the leaving group in a reaction significantly influences the rate and outcome of nucleophilic substitution reactions.

- Specific nucleophilic reaction mechanisms: Delving into the detailed mechanisms of SN1 and SN2 reactions, among others, will provide a deeper understanding of nucleophile participation.

By understanding the fundamentals of nucleophilicity and the factors that influence it, you'll be well-equipped to identify nucleophiles and non-nucleophiles with confidence. This knowledge is not only essential for academic pursuits but also for various applications in the chemical sciences and related fields. Remember to always consider the context of the reaction when analyzing the nucleophilic properties of a given molecule.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Identification Of Selected Anions Lab Answers

Mar 15, 2025

-

All Of The Following Are Manufacturing Costs Except

Mar 15, 2025

-

Jess Notices A Low Fuel Light

Mar 15, 2025

-

Draw An Outer Electron Box Diagram For A Cation

Mar 15, 2025

-

The Image Depicts What Mechanism Of Evolution

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Of The Following Is Not A Nucleophile Chegg . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.