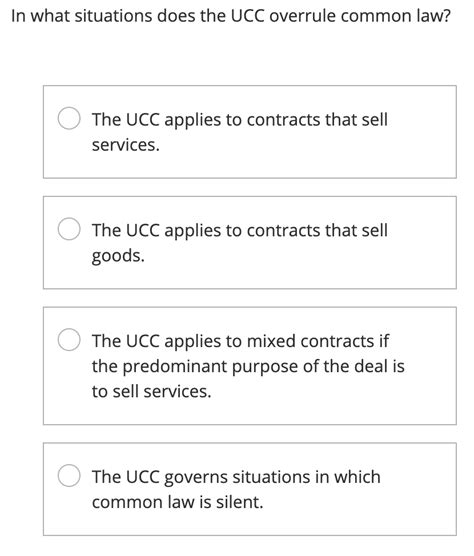

In What Situations Does The Ucc Overrule Common Law

Holbox

Mar 18, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

When Does the UCC Overrule Common Law? Navigating the Intersection of Contract Law

The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) is a comprehensive set of laws governing commercial transactions in the United States. While it aims to standardize commercial law across states, it doesn't entirely replace common law. Instead, it interacts with and often supersedes common law principles in specific areas of contract law. Understanding when and how the UCC overrules common law is crucial for businesses and legal professionals alike. This article delves deep into this complex interplay, exploring various scenarios where UCC provisions take precedence.

The Scope of UCC Applicability: Where Common Law Still Reigns

Before exploring instances of UCC override, it's vital to understand the UCC's limitations. It doesn't govern all contracts. Common law of contracts continues to govern transactions outside the UCC's purview. This typically includes contracts for:

- Real estate: The sale of land and related interests are primarily governed by common law, though certain aspects might involve UCC principles if personal property is also part of the transaction (e.g., fixtures).

- Service contracts: Contracts focusing solely on the provision of services generally fall under common law.

- Employment contracts: These contracts are generally outside the scope of the UCC, with exceptions potentially arising in specific circumstances relating to intellectual property or goods involved in employment duties.

- Contracts involving intangible property: Contracts concerning intellectual property, copyrights, patents, or other intangible assets typically are not governed by the UCC.

The distinction often lies in whether the contract's primary subject matter is the sale of goods as defined by the UCC.

UCC Article 2: The Heart of the Matter – Sales of Goods

Article 2 of the UCC, specifically Article 2-105, defines “goods” as movable, tangible personal property. This seemingly straightforward definition leads to many nuanced interpretations. Consider these factors:

-

Mixed contracts: Contracts involving both goods and services can be tricky. Courts often apply the predominant purpose test to determine which law applies. If the contract's primary purpose is the sale of goods, the UCC governs; if the primary purpose is services, common law applies. This test, however, can be subjective and fact-dependent, leading to varying outcomes.

-

Goods versus intangibles: Distinguishing between tangible goods and intangible property remains critical. Software licenses, for instance, have been subject to extensive litigation, with courts grappling to determine whether they are goods or services. Similarly, the sale of digital downloads often raises the question of whether the primary subject matter is a "good" or an intangible right.

-

Future goods: The UCC also applies to contracts involving goods not yet in existence. This creates complexities in terms of risk allocation and warranties, particularly when considering the possibility of future changes in the market or technology.

Key Areas Where the UCC Overrules Common Law

When the UCC applies, it often preempts or modifies common law principles. Here are significant examples:

1. Statute of Frauds:

The UCC's Statute of Frauds (UCC 2-201) differs from common law's. While common law usually requires all contracts to be in writing to be enforceable, the UCC only demands it for certain sales of goods contracts. Specifically, those contracts exceeding a certain value (often $500) must be evidenced by a signed writing. Crucially, the UCC allows for exceptions, such as partial performance or admission in court, making it more flexible than the stringent common law approach.

2. Formation of Contracts:

The UCC often offers a more flexible approach to contract formation than common law. It introduces concepts like firm offers (UCC 2-205) that, under certain conditions, make an offer irrevocable for a specified period, even without consideration. This contrasts with traditional common law principles, where offers are generally revocable at any time before acceptance.

The concept of battle of the forms (UCC 2-207) presents another significant deviation. Common law usually adheres strictly to the “mirror image rule,” requiring acceptance to precisely mirror the offer. The UCC, however, allows for contracts to be formed even if the acceptance contains additional or different terms, provided these terms don't materially alter the contract.

3. Warranties:

The UCC creates an implied warranty of merchantability (UCC 2-314) for merchants selling goods in the ordinary course of business. This warranty ensures that the goods are fit for their ordinary purpose. Similarly, an implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose (UCC 2-315) arises when a seller knows the buyer's specific needs and recommends a product to meet those needs. These warranties are not necessarily explicitly stated but are implied by law, expanding buyer protection beyond strict common law approaches.

Furthermore, the UCC provides a framework for disclaiming warranties, offering a more structured and regulated approach compared to the more ambiguous common law approach.

4. Risk of Loss:

The UCC addresses risk of loss in sales contracts more explicitly than common law. It provides detailed rules based on factors such as the type of delivery, the seller's and buyer's actions, and the presence of a breach. UCC 2-509 and 2-510 lay down specific rules determining which party bears the risk of loss in various scenarios, offering clarity and predictability that common law often lacks.

5. Remedies:

The UCC provides a broader range of remedies for breach of contract than common law. It allows for cover (buying substitute goods) and specific performance (forcing the breaching party to fulfill the contract), actions not always readily available under common law. The UCC also provides for liquidated damages clauses (UCC 2-718), allowing parties to pre-determine damages in case of breach, simplifying the process of remedy determination.

6. Perfect Tender Rule:

While the common law’s concept of “substantial performance” allows for minor deviations in contract fulfillment, the UCC originally introduced the “perfect tender rule” (UCC 2-601). This meant that goods delivered had to conform precisely to the contract’s specifications; any deviation gave the buyer the right to reject the goods. However, the UCC has since evolved, and courts apply the rule with more flexibility, acknowledging the importance of commercial reasonableness. Nevertheless, the original stricter stance remains a point of difference from common law.

Navigating the Complexities: Practical Implications

The interplay between the UCC and common law isn't always straightforward. Many cases involve complex fact patterns that require careful analysis to determine the applicable law. Consider these practical implications:

-

Careful drafting: Contracts involving goods need meticulous drafting to clearly identify the goods, specify terms of delivery, and address warranties and remedies. Ambiguity can lead to disputes and costly litigation.

-

Understanding the predominant purpose test: When contracts involve both goods and services, identifying the predominant purpose is crucial. This determination significantly impacts which legal framework applies. Ambiguous contracts may trigger judicial interpretation focused on the central nature of the transaction.

-

Seeking legal advice: Given the complexities of UCC application, seeking legal counsel is essential. Experienced lawyers can analyze the specific facts of a transaction and advise on the appropriate legal framework and the best strategies for contract formation and enforcement.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Interaction

The UCC's relationship with common law is not one of simple replacement but rather a dynamic interaction. While the UCC supersedes common law in specific areas involving the sale of goods, common law retains its importance in contracts primarily concerning services, real estate, and intangible property. Understanding the distinctions, the nuances of UCC Article 2, and the ways the UCC modifies or supersedes common law principles is paramount for businesses and legal professionals alike to navigate the complexities of commercial transactions effectively and minimize legal risks. Ongoing developments in technology and commercial practices continuously shape the ongoing evolution of both common law and the UCC, making vigilance and legal expertise essential for ensuring compliance and protecting commercial interests.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Best Known Self Regulatory Group Is The Blank

Mar 18, 2025

-

Your Local Movie Theater Uses The Same Group Pricing Strategy

Mar 18, 2025

-

A Set Of Bivariate Data Was Used To Create

Mar 18, 2025

-

What Is The Product Of This Reaction

Mar 18, 2025

-

Record The Entry To Close The Dividends Account

Mar 18, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about In What Situations Does The Ucc Overrule Common Law . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.