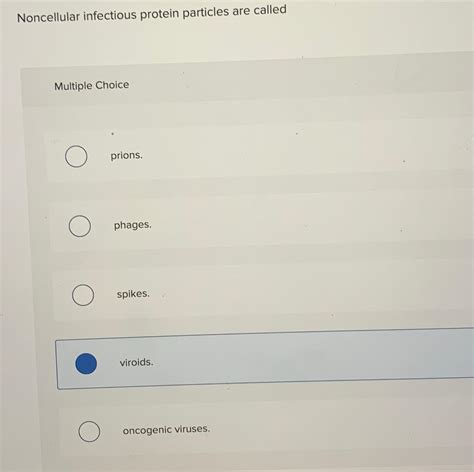

Noncellular Infectious Protein Particles Are Called

Holbox

Mar 17, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Noncellular Infectious Protein Particles Are Called Prions: A Deep Dive into Their Nature, Mechanisms, and Impact

Noncellular infectious protein particles are called prions. These unique agents stand apart from traditional infectious pathogens like viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Unlike these cellular organisms, prions lack nucleic acids (DNA or RNA), the genetic material that directs the replication and function of most infectious agents. This fundamental difference makes prions a fascinating and challenging subject of study in biology and medicine. This article will delve into the intricacies of prions, exploring their structure, mechanisms of infection, associated diseases, and current research efforts aimed at understanding and combating these enigmatic agents.

Understanding Prion Structure and Function

Prions are misfolded versions of normal cellular proteins. The normal cellular form, designated PrP<sup>C</sup> (cellular prion protein), is found on the surface of many cells, particularly neurons in the brain and other nervous system tissues. Its exact function remains a subject of ongoing research, but hypotheses suggest roles in cell signaling, copper metabolism, and neuronal protection. The key feature differentiating PrP<sup>C</sup> from its infectious counterpart is its conformation, or three-dimensional structure. PrP<sup>C</sup> is predominantly α-helical, while the infectious prion protein, PrP<sup>Sc</sup> (scrapie prion protein), is characterized by a high proportion of β-sheets. This seemingly minor difference has profound consequences.

The Misfolding Cascade: A Key to Prion Propagation

The transition from PrP<sup>C</sup> to PrP<sup>Sc</sup> is crucial to the infectious process. This misfolding is thought to be a self-perpetuating event: a single PrP<sup>Sc</sup> molecule can interact with a PrP<sup>C</sup> molecule, inducing a conformational change that converts the latter into another PrP<sup>Sc</sup> molecule. This process creates a chain reaction, where a single infectious prion can lead to the accumulation of vast numbers of misfolded proteins. This accumulation is a hallmark of prion diseases and is responsible for the cellular damage and neurological dysfunction they cause.

The exact mechanism of this conformational conversion remains an area of active investigation. However, it is believed to involve specific interactions between the amino acid residues of PrP<sup>C</sup> and PrP<sup>Sc</sup>. Furthermore, the process can be influenced by various factors, including genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and potentially other cellular factors.

Prion Diseases: A Spectrum of Neurological Degenerations

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are a group of fatal neurodegenerative disorders affecting both humans and animals. These diseases are characterized by the progressive accumulation of PrP<sup>Sc</sup> in the brain, leading to neuronal damage, spongiform changes (the formation of vacuoles or holes in the brain tissue), and ultimately, death.

Human Prion Diseases

Several human prion diseases exist, each with distinct clinical presentations and potential modes of transmission:

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD): This is the most common human prion disease, with several subtypes including sporadic CJD (sCJD), the most frequent form with no known cause; familial CJD (fCJD), inherited through genetic mutations; and iatrogenic CJD (iCJD), acquired through medical procedures.

- Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD): This is linked to consumption of beef contaminated with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as "mad cow disease."

- Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker Syndrome (GSS): A rare, inherited prion disease characterized by ataxia (lack of muscle coordination) and dementia.

- Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI): A very rare inherited prion disease primarily affecting the thalamus, leading to progressive insomnia and severe neurological dysfunction.

- Kuru: Historically, this disease was prevalent among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea and was linked to ritualistic cannibalism.

Animal Prion Diseases

Prion diseases also affect animals, with significant economic and public health implications:

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE): "Mad cow disease" gained notoriety in the 1980s and 1990s due to its impact on the cattle industry and its potential transmission to humans (vCJD).

- Scrapie: This disease affects sheep and goats.

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD): This prion disease affects cervids (deer, elk, and moose).

- Transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME): This disease is seen in farmed mink.

Mechanisms of Prion Transmission and Infection

Prion diseases can be transmitted through several routes:

- Genetic Predisposition: Mutations in the PRNP gene, which encodes PrP<sup>C</sup>, can increase the risk of developing prion diseases, especially familial forms.

- Sporadic Cases: The majority of sCJD cases appear spontaneously without a clear cause, suggesting a sporadic misfolding event might trigger the disease.

- Iatrogenic Transmission: Accidental exposure to infected tissues or medical instruments can result in iCJD. This highlights the importance of rigorous sterilization procedures in healthcare settings.

- Dietary Transmission: Ingestion of contaminated meat products, as seen with vCJD linked to BSE, demonstrates the potential for dietary transmission of prions.

The remarkable stability of PrP<sup>Sc</sup> contributes to its infectivity. It is resistant to degradation by proteases (enzymes that break down proteins), heat, and many disinfectants. This resilience makes prions incredibly difficult to inactivate, posing significant challenges for infection control and waste management.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Prion Diseases

Diagnosing prion diseases is challenging due to the insidious nature of the illness and the lack of specific diagnostic markers. Diagnosis often relies on a combination of clinical symptoms, neurological examination, EEG (electroencephalogram) findings, and brain imaging (MRI). However, definitive diagnosis typically requires post-mortem analysis of brain tissue to identify the presence of PrP<sup>Sc</sup>.

Unfortunately, there is currently no effective treatment or cure for prion diseases. Once the symptoms manifest, the progression is typically rapid and fatal. Research efforts are focused on developing therapeutic strategies targeting PrP<sup>Sc</sup> formation, aggregation, or clearance. Potential approaches under investigation include:

- Drugs that inhibit PrP<sup>Sc</sup> formation: These drugs could potentially block the conformational change from PrP<sup>C</sup> to PrP<sup>Sc</sup>.

- Antibodies that target PrP<sup>Sc</sup>: These antibodies could help clear PrP<sup>Sc</sup> from the brain.

- Strategies to enhance PrP<sup>Sc</sup> clearance: Approaches to improve the body's natural mechanisms for clearing misfolded proteins.

Current Research and Future Directions

Research on prions continues to be a dynamic and rapidly evolving field. Scientists are exploring various aspects of prion biology, including:

- The precise mechanism of PrP<sup>Sc</sup> formation: Understanding the molecular details of this process is critical for developing effective therapeutic interventions.

- The role of cellular cofactors in prion propagation: Identifying cellular factors that facilitate PrP<sup>Sc</sup> formation could offer new therapeutic targets.

- Developing sensitive diagnostic tools: Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for improving patient outcomes, and new diagnostic methods are constantly being developed.

- Exploring potential prophylactic strategies: Preventing prion infection is of paramount importance, and research is underway to identify ways to protect against prion exposure.

- Comparative studies across different prion strains and species: Understanding the diversity of prions and their adaptation to different hosts is essential for developing broadly effective interventions.

The unique nature of prions presents both significant challenges and exciting opportunities for scientific discovery. As our understanding of these infectious agents deepens, we can anticipate further advancements in diagnostics, therapeutics, and prevention strategies to combat the devastating effects of prion diseases. The ultimate goal is to develop effective interventions to prevent, delay, or halt the progression of these currently incurable neurological disorders. The future of prion research holds immense promise for advancing our understanding of protein misfolding diseases and developing innovative therapeutic approaches not only for prion diseases but also for other neurodegenerative disorders sharing similar underlying mechanisms. Continued research in this field is crucial for safeguarding public health and improving the lives of those affected by these devastating illnesses.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Lewis Structure For Po Oh 3

Mar 17, 2025

-

Label The Components Of A Myofibril

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Do Pumice And Scoria Have In Common

Mar 17, 2025

-

Classify Each Substance Based On The Intermolecular Forces

Mar 17, 2025

-

A Person In Charge Should Be Able To Identify Signs

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Noncellular Infectious Protein Particles Are Called . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.