The Scientific Process Is Involving Both

Holbox

Mar 21, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- The Scientific Process Is Involving Both

- Table of Contents

- The Scientific Process: A Dance Between Deduction and Induction

- Deduction: From General Principles to Specific Predictions

- Induction: From Specific Observations to General Principles

- The Interplay of Deduction and Induction: A Cyclical Process

- The Role of Falsification and Refutation

- Conclusion: A Dynamic and Iterative Process

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

The Scientific Process: A Dance Between Deduction and Induction

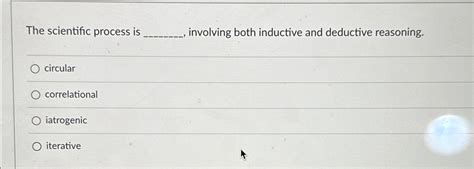

The scientific process, often romanticized as a linear progression from observation to conclusion, is in reality a complex and iterative dance between two powerful modes of reasoning: deduction and induction. While seemingly distinct, these methods are inextricably intertwined, each informing and refining the other in a continuous cycle that drives scientific discovery. Understanding this interplay is crucial to grasping the true nature of scientific inquiry and its remarkable capacity to unravel the mysteries of the universe.

Deduction: From General Principles to Specific Predictions

Deductive reasoning, at its core, is a top-down approach. It begins with established general principles or theories and uses logic to deduce specific predictions or consequences. If the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. This certainty is the hallmark of deductive reasoning, providing a powerful tool for testing existing theories.

Example:

- Premise 1: All men are mortal.

- Premise 2: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

In science, deductive reasoning often takes the form of hypothesis testing. A scientist might formulate a hypothesis based on a broader theory. They then design an experiment to test whether the hypothesis holds true under specific conditions. If the experimental results contradict the hypothesis, the underlying theory may need revision or rejection. However, if the results support the hypothesis, it strengthens the theory's validity, but doesn't definitively prove it.

Strengths of Deductive Reasoning in Science:

- Provides testable predictions: Deduction allows scientists to generate specific, falsifiable predictions that can be tested through observation or experimentation.

- Offers strong conclusions (given true premises): When premises are true, deductive conclusions are guaranteed to be true, providing a robust foundation for scientific knowledge.

- Facilitates precise testing: Deductive reasoning allows for the focused testing of specific aspects of a theory, leading to more efficient and targeted research.

Limitations of Deductive Reasoning in Science:

- Relies on pre-existing knowledge: Deductive reasoning cannot generate new knowledge on its own; it requires established theories or principles as starting points.

- Can be limited by inaccurate premises: If the initial premises are incorrect, the conclusion, no matter how logically sound, will also be incorrect.

- Doesn't directly lead to new theories: Deduction excels at testing existing theories but isn't a primary source of generating novel theoretical frameworks.

Induction: From Specific Observations to General Principles

Inductive reasoning, conversely, is a bottom-up approach. It starts with specific observations or data and then works towards formulating broader generalizations or theories. Unlike deduction, induction doesn't guarantee the truth of its conclusions; it only suggests a probable conclusion based on available evidence. The more evidence supports a generalization, the stronger the inductive argument becomes, but there's always the possibility of encountering contradictory evidence in the future.

Example:

- Observation 1: Swan 1 is white.

- Observation 2: Swan 2 is white.

- Observation 3: Swan 3 is white.

- Conclusion: Therefore, all swans are probably white. (This conclusion was famously shown to be false upon the discovery of black swans.)

In science, induction is crucial for generating hypotheses and formulating new theories. Scientists collect data through observations, experiments, and analyses. They then identify patterns, trends, and correlations within the data to formulate general principles or theories that explain the observed phenomena.

Strengths of Inductive Reasoning in Science:

- Generates new hypotheses and theories: Induction is essential for creating novel scientific frameworks and extending the boundaries of existing knowledge.

- Deals with uncertainty: Inductive reasoning embraces the inherent uncertainty in scientific inquiry, acknowledging that conclusions are probabilistic rather than definitive.

- Adaptable to new evidence: As new data emerges, inductive generalizations can be revised, refined, or even rejected to accommodate the evolving understanding of a phenomenon.

Limitations of Inductive Reasoning in Science:

- Conclusions are probabilistic, not certain: Inductive arguments can only suggest the likelihood of a conclusion, not guarantee its truth.

- Susceptible to bias: The selection of data, the interpretation of patterns, and the formulation of generalizations can be influenced by researcher bias.

- Can lead to inaccurate generalizations: A limited or biased sample of data can lead to inaccurate or misleading generalizations.

The Interplay of Deduction and Induction: A Cyclical Process

The scientific process isn't merely a linear progression; it's a dynamic interplay between deduction and induction. These two modes of reasoning operate in a cyclical fashion, constantly informing and refining each other.

1. Observation and Induction: The process frequently begins with observations of the natural world. Through inductive reasoning, scientists identify patterns and formulate hypotheses or preliminary theories.

2. Hypothesis Testing and Deduction: The formulated hypothesis is then tested using deductive reasoning. The hypothesis generates predictions, and experiments are designed to test these predictions.

3. Data Analysis and Induction: The experimental results are analyzed, and new patterns are sought. This leads back to induction, where the initial hypothesis is refined, modified, or even replaced based on the new evidence.

4. Theory Building and Deduction: Over time, repeated cycles of induction and deduction lead to the development of more robust and comprehensive theories. These theories can then be used to generate new hypotheses, leading to further cycles of testing and refinement. This iterative process continues, with each cycle building upon the previous ones, gradually improving our understanding of the natural world.

Examples of the Interplay in Action:

- The development of the theory of evolution: Darwin's observations of species variation (induction) led to the hypothesis of natural selection (deduction). Subsequent testing of this hypothesis (deduction) through fossil evidence, comparative anatomy, and molecular biology (induction) continuously refined and strengthened the theory of evolution.

- The discovery of the structure of DNA: Early observations of DNA's chemical composition (induction) suggested a helical structure. This hypothesis (deduction) was later confirmed through X-ray diffraction patterns (induction), leading to the development of the double helix model.

The Role of Falsification and Refutation

A crucial aspect of the scientific process is the concept of falsification, proposed by Karl Popper. While scientific theories can never be definitively proven true, they can be falsified – that is, shown to be false. The ability of a theory to generate testable predictions that could potentially disprove it is a hallmark of a scientific theory. This emphasis on falsifiability helps to ensure that scientific knowledge is constantly being tested and refined. A theory that withstands numerous attempts at falsification becomes more robust and credible. However, even the most well-established theories are always subject to revision or rejection in the face of compelling new evidence.

Conclusion: A Dynamic and Iterative Process

The scientific process is not a straightforward, linear path. Instead, it's a dynamic, iterative journey involving the continuous interplay of deduction and induction. These two modes of reasoning work in concert, propelling scientific inquiry forward. Deduction provides a rigorous framework for testing existing theories, while induction allows for the generation of new hypotheses and theories. This cyclical process, combined with the principle of falsification, ensures that scientific knowledge is constantly being challenged, refined, and improved. It's this continuous cycle of testing, refining, and revising that has allowed science to achieve its remarkable success in understanding the complexities of the universe. The dance between deduction and induction isn't just a methodological detail; it is the very essence of the scientific enterprise.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Primary Organizational Buying Objective For Business Firms Is To

Mar 28, 2025

-

A Statement Of Comprehensive Income Does Not Include

Mar 28, 2025

-

Use The Following Cell Phone Airport Data

Mar 28, 2025

-

Slack Is An Example Of Collaboration Software True Or False

Mar 28, 2025

-

If A Person Is Severely Dehydrated Their Extracellular

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Scientific Process Is Involving Both . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.