The Relationship Between Rich Southern Planters And Poor Southern Farmers

Holbox

Mar 22, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- The Relationship Between Rich Southern Planters And Poor Southern Farmers

- Table of Contents

- The Complex Relationship Between Rich Southern Planters and Poor Southern Farmers

- The Economic Dependence of Poor Farmers

- Credit and Debt:

- Market Access:

- Land Ownership and Labor:

- Shared Identities and Cultural Bonds

- Religion and Community:

- Political Ideology:

- Racial Hierarchy:

- Tensions and Conflicts

- Political Representation:

- Economic Exploitation:

- Social Status and Hierarchy:

- The Threat of Upward Mobility:

- The Impact of Slavery

- Competition for Labor:

- Racial Division and Solidarity:

- Social Control:

- The Legacy of the Relationship

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

The Complex Relationship Between Rich Southern Planters and Poor Southern Farmers

The antebellum South is often romanticized, conjuring images of sprawling plantations and gracious living. However, this idyllic picture obscures a deeply stratified society characterized by stark economic and social inequalities. At the heart of this system lay the complex and often fraught relationship between the wealthy planter class and the much larger population of poor white farmers. This wasn't a monolithic relationship; it varied across regions, and individual experiences defied easy categorization. However, several key themes consistently shaped their interactions.

The Economic Dependence of Poor Farmers

The economic system of the antebellum South was fundamentally built upon the institution of slavery and the production of cash crops like cotton, tobacco, and rice. While wealthy planters owned vast tracts of land and numerous enslaved people, generating immense wealth, the majority of white Southerners owned little or no land and lived a precarious existence. These poor farmers, often called yeoman farmers, were economically dependent on the planter class in several ways:

Credit and Debt:

Planters often controlled local economies, owning stores, mills, and other businesses. Poor farmers frequently relied on credit from these planters to purchase seeds, tools, and supplies. This system, however, often trapped them in a cycle of debt. High interest rates and fluctuating commodity prices made it difficult for them to repay loans, leaving them perpetually indebted to the planter elite. This economic dependence fostered a sense of obligation and deference, limiting their social and political agency.

Market Access:

Planters often controlled access to markets, dictating prices and terms of trade. Poor farmers were at their mercy, forced to accept lower prices for their crops or face the difficulties of transporting their goods to distant markets. This unequal power dynamic further reinforced the economic vulnerability of the yeoman farmer.

Land Ownership and Labor:

While some poor farmers owned small plots of land, many worked as tenants or sharecroppers on planter land. Tenancy involved renting land from a planter, while sharecropping involved working the land in exchange for a share of the crop. Both systems kept poor farmers economically dependent, with little control over their production and profits. This system often left them with a meager living, barely scraping by at the subsistence level.

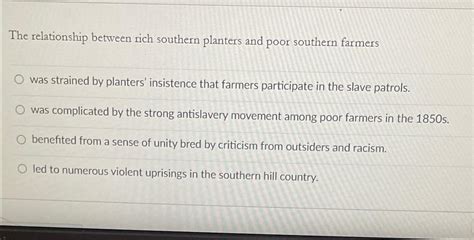

Shared Identities and Cultural Bonds

Despite the economic disparity, some shared cultural bonds existed between planters and poor farmers. Both groups considered themselves part of a distinct "Southern" identity, which often set them apart from Northerners. This shared identity was rooted in common experiences, traditions, and cultural values. This commonality wasn't always a harmonious relationship, but it did provide a backdrop against which other dynamics played out.

Religion and Community:

Religion played a significant role in the lives of both planters and poor farmers. Many attended the same churches and participated in shared religious rituals. This provided a sense of community and solidarity, which sometimes transcended class boundaries. However, even within religious communities, the social hierarchy remained apparent. Planters generally occupied positions of leadership and influence within the church.

Political Ideology:

While planters held more political power, poor farmers often shared similar political ideals, particularly when it came to states' rights and opposition to federal interference. This shared political ideology occasionally forged a temporary alliance, but it was often overshadowed by the fundamental economic inequalities between them.

Racial Hierarchy:

Both planters and poor farmers shared a common interest in maintaining the racial hierarchy. They understood that their relative social positions depended upon the existence of slavery and white supremacy. This shared interest in racial dominance often fostered a degree of solidarity, although the benefits of this system were distributed very unevenly.

Tensions and Conflicts

Despite shared aspects of their identity, tensions and conflicts were unavoidable between planters and poor farmers. The vast economic disparity and the power imbalance created a breeding ground for resentment and conflict.

Political Representation:

The planter class dominated Southern politics. While poor farmers could vote, their political influence was limited. Planters wielded significant power through their wealth, influence, and control over the political apparatus. This imbalance of power led to policies that favored the planter class, often at the expense of the poor farmers.

Economic Exploitation:

The system of credit, tenancy, and sharecropping inherent in the Southern economy led to the continued exploitation of poor farmers. Planters often manipulated the system to maintain their economic dominance, leaving poor farmers trapped in a cycle of debt and poverty. This led to widespread resentment and occasional resistance.

Social Status and Hierarchy:

Despite shared cultural aspects, the planter class maintained a distinct social hierarchy that excluded poor farmers from many aspects of their lives. Social gatherings, political participation, and access to elite institutions were mostly limited to the planter elite. This social separation highlighted and reinforced the economic inequalities.

The Threat of Upward Mobility:

The economic success of a small number of poor farmers who managed to accumulate land and wealth occasionally threatened the stability of the planter elite. This created a tension where the planters sometimes worked actively to maintain the system that kept most poor farmers in their place. The success stories were outliers, reminding the majority of their limited prospects.

The Impact of Slavery

The institution of slavery profoundly impacted the relationship between planters and poor white farmers. While slavery primarily benefited the planter class, it also had significant consequences for poor farmers:

Competition for Labor:

The use of enslaved labor by planters created competition for paid labor. The availability of free (unpaid) enslaved labor often drove down wages for poor white farmers who did hire labor.

Racial Division and Solidarity:

Slavery created a racial divide that, while initially beneficial for white farmers, became increasingly fragile. The planters' control over the political and economic systems reinforced white supremacy but also created an undercurrent of resentment among poor whites, who sometimes felt exploited and used by the planter elite.

Social Control:

The pervasive presence of slavery served as a social control mechanism for both planters and poor farmers. The fear of slave uprisings and the constant threat of social upheaval worked to maintain the existing social order, which served the interests of the wealthy but also offered a sense of security, albeit a limited one, for poor white farmers.

The Legacy of the Relationship

The relationship between rich Southern planters and poor Southern farmers was complex and multifaceted. While economic dependence, shared cultural aspects, and even racial solidarity existed, these were often overshadowed by deep-seated inequalities and unresolved tensions. This historical relationship continues to inform contemporary discussions about race, class, and economic inequality in the American South and beyond. The legacy of this system lives on in the continued disparities in wealth and opportunity that persist in many parts of the region. Understanding the intricacies of this historical dynamic is crucial to grasping the complexities of American history and the enduring challenges of achieving a more just and equitable society. The narrative is not simply one of exploitation but a nuanced interplay of economic dependence, shared cultural bonds, and simmering resentments that ultimately shaped the fabric of the antebellum South and its enduring legacy.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Decrease In The Price Of A Good Will

Mar 24, 2025

-

Correctly Label The Following Anatomical Features Of A Nerve

Mar 24, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Uses Of Removable Media Is Appropriate

Mar 24, 2025

-

The Lack Of Consensus About The Correct Diagnosis

Mar 24, 2025

-

Crafting And Executing Strategy Concepts And Cases

Mar 24, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about The Relationship Between Rich Southern Planters And Poor Southern Farmers . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.