Pre Lab Exercise 24-3 Digestive Enzymes

Holbox

Mar 13, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Pre-Lab Exercise 24-3: Digestive Enzymes: A Deep Dive into Enzymatic Action and Digestion

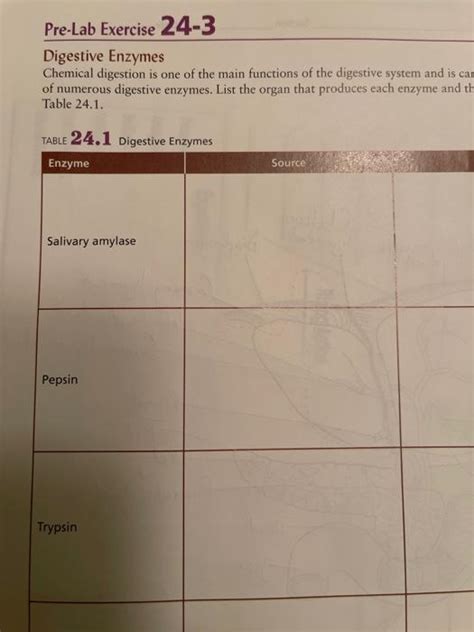

Understanding the intricacies of digestion requires a solid grasp of the enzymes involved. This pre-lab exercise focuses on digestive enzymes, their specific functions, and the factors that influence their activity. Mastering this material is crucial for comprehending the complex biochemical processes that break down food for absorption and energy production.

I. Introduction to Digestive Enzymes

Digestion, the process of breaking down large food molecules into smaller, absorbable units, heavily relies on a specialized group of proteins known as enzymes. These biological catalysts accelerate the rate of chemical reactions without being consumed in the process. Digestive enzymes are categorized based on the type of macromolecule they target: carbohydrates, proteins, or lipids.

A. Carbohydrate Digestion

Carbohydrate digestion begins in the mouth with salivary amylase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes starch into smaller polysaccharides and disaccharides. This initial breakdown continues in the small intestine, where pancreatic amylase further degrades starch. Other enzymes, including maltase, sucrase, and lactase, located in the intestinal lining, complete the process by breaking down disaccharides (maltose, sucrose, and lactose) into monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose), which can then be absorbed into the bloodstream.

B. Protein Digestion

Protein digestion begins in the stomach with the action of pepsin, an enzyme activated by the acidic environment of the stomach. Pepsin initiates the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides. In the small intestine, pancreatic enzymes such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, and carboxypeptidase continue this process, generating smaller peptides and amino acids. Finally, brush-border enzymes, including aminopeptidases and dipeptidases, located within the intestinal lining, complete the hydrolysis of peptides into individual amino acids ready for absorption.

C. Lipid Digestion

Lipid digestion is unique due to the hydrophobic nature of lipids. The process begins in the small intestine, where bile salts emulsify fats, increasing their surface area for enzymatic action. Pancreatic lipase, the primary enzyme involved, breaks down triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol. These smaller molecules, along with monoglycerides, are then absorbed into the intestinal cells.

II. Factors Affecting Enzyme Activity

The activity of digestive enzymes is highly sensitive to various environmental factors. Understanding these influences is crucial for predicting and interpreting experimental results.

A. Temperature

Enzymes have an optimal temperature range for maximum activity. Beyond this range, their structure can denature, leading to a loss of function. Digestive enzymes in humans operate most efficiently around body temperature (37°C). Higher temperatures cause denaturation, whereas lower temperatures slow down reaction rates.

B. pH

The pH of the environment significantly impacts enzyme activity. Each enzyme has an optimal pH range. For example, pepsin, active in the stomach's acidic environment, functions optimally at a low pH (around 2). In contrast, pancreatic enzymes, active in the alkaline environment of the small intestine, function best at a slightly alkaline pH (around 8).

C. Substrate Concentration

Enzyme activity is directly proportional to substrate concentration up to a certain point. At low substrate concentrations, the reaction rate increases linearly with substrate concentration as more enzyme molecules are available to bind to substrate molecules. However, at high substrate concentrations, the enzyme becomes saturated, and the reaction rate plateaus, even if more substrate is added. The reaction rate is then limited by the amount of enzyme available.

D. Enzyme Concentration

Similar to substrate concentration, enzyme concentration also plays a crucial role. Increasing the enzyme concentration increases the reaction rate until the substrate becomes limiting factor. This is because, with more enzyme molecules, more substrate-enzyme complexes can form, leading to an increase in product formation. However, beyond a certain point, increasing the enzyme concentration will no longer increase the reaction rate as the available substrate has become a limiting factor.

E. Inhibitors

Enzyme inhibitors are molecules that decrease enzyme activity. They can be competitive or non-competitive. Competitive inhibitors resemble the substrate and compete for binding to the active site. Non-competitive inhibitors bind to the enzyme at a site other than the active site, altering the enzyme's shape and reducing its activity. Many drugs and toxins act as enzyme inhibitors.

III. Experimental Design Considerations

A successful experiment investigating digestive enzyme activity requires careful planning and execution. Here are some key considerations:

A. Selecting Appropriate Enzymes and Substrates

The choice of enzyme and substrate depends on the specific process being investigated. For instance, to study carbohydrate digestion, starch and amylase would be suitable choices. Similarly, for protein digestion, protein and pepsin/trypsin can be used, and for lipid digestion, lipids and lipase would be appropriate.

B. Controlling Variables

Maintaining precise control over experimental conditions is essential to obtain reliable results. Factors like temperature, pH, substrate concentration, and enzyme concentration must be carefully monitored and controlled. Using control groups without enzymes or with inactive enzymes is crucial for comparative analysis.

C. Measuring Enzyme Activity

Measuring enzyme activity involves quantifying the rate of substrate conversion into product. This can be achieved through various methods, depending on the specific enzyme and substrate. For example, measuring the reducing sugars produced from starch hydrolysis via Benedict's reagent, or using spectrophotometric techniques to measure the absorbance of coloured products.

D. Data Analysis and Interpretation

After obtaining the experimental data, appropriate statistical analysis must be employed to determine the significance of the results. Graphs and tables should be used to present the findings clearly. The results should be interpreted in the context of the factors affecting enzyme activity, and any deviations from expected results should be carefully evaluated and discussed.

IV. Practical Applications

Understanding digestive enzymes has wide-ranging practical applications in various fields, including:

A. Medicine

Digestive enzyme deficiencies, such as lactose intolerance (lactase deficiency) and pancreatic insufficiency, can lead to digestive problems. Enzyme replacement therapies, involving oral administration of specific digestive enzymes, are commonly used to alleviate these conditions. Understanding enzyme kinetics aids in developing effective drug treatments that target specific enzymes involved in disease processes.

B. Food Industry

Enzymes are widely used in the food industry for various purposes, including improving the quality and texture of food products. Amylases and proteases are utilized in baking and brewing industries. Lipases are used in the production of cheese and other dairy products.

C. Biotechnology

Enzymes are essential tools in biotechnology for various applications, including biofuel production and environmental remediation. Genetically modified microorganisms are employed to produce large quantities of specific enzymes for industrial applications.

V. Conclusion

Digestive enzymes play a critical role in the breakdown of food, making essential nutrients available for absorption and energy production. A thorough understanding of their functions, the factors influencing their activity, and their practical applications is crucial in various fields, including medicine, food science, and biotechnology. This pre-lab exercise serves as a foundational step towards a more comprehensive understanding of these vital biomolecules and their role in maintaining health and well-being. This knowledge allows for the development of strategies to address digestive disorders and enhance food production processes. Further research and exploration into the intricate world of enzymes promise even greater advancements in these areas. By thoroughly understanding the principles outlined in this pre-lab exercise, you will be well-equipped to design and execute experiments that provide valuable insights into the fascinating world of digestive enzymes. Remember to always prioritize safety and follow appropriate laboratory procedures when conducting experiments. The meticulous attention to detail in experimental design and data analysis is crucial for obtaining accurate and reliable results, ensuring the successful completion of this pre-lab exercise and future scientific endeavors. Through this exercise, we aim to foster a strong foundation in understanding the intricate processes of digestion and the critical role enzymes play within this complex system. Remember, the power of knowledge is in its application, and understanding digestive enzymes empowers us to address many health challenges and enhance numerous industries.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Can Tyrosine Form Hydrogen Bonds With Its Side Chain

Mar 13, 2025

-

When The Carbonyl Group Of A Ketone Is Protonated

Mar 13, 2025

-

Based On The Industry Low Industry Average And Industry High Values

Mar 13, 2025

-

Question Sting Select The Correct Configuration

Mar 13, 2025

-

When Distrtibutoers Do Now Have Authorzation

Mar 13, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Pre Lab Exercise 24-3 Digestive Enzymes . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.