Filtrate First Passes From The Glomerular Capsule To The

Holbox

Mar 24, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

- Filtrate First Passes From The Glomerular Capsule To The

- Table of Contents

- The Glomerular Filtrate's Journey: From Bowman's Capsule to the Final Urine

- The Glomerulus: The Filtration Powerhouse

- Hydrostatic Pressure: The Driving Force

- Oncotic Pressure: The Counterforce

- Bowman's Capsule Hydrostatic Pressure: The Restraint

- Net Filtration Pressure: The Decisive Factor

- Bowman's Capsule: The Initial Collection Point

- The Renal Tubule: Fine-Tuning the Filtrate

- Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT): Reabsorption Central

- Loop of Henle: Concentrating the Urine

- Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT): Fine-tuning and Hormonal Regulation

- Collecting Duct: Final Adjustments and Urine Formation

- From Filtrate to Urine: The Final Product

- Factors Affecting Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

- Clinical Significance: Understanding GFR for Disease Diagnosis

- Conclusion: A Complex and Vital Process

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

The Glomerular Filtrate's Journey: From Bowman's Capsule to the Final Urine

The human body is a marvel of intricate engineering, and the urinary system stands as a testament to this complexity. At the heart of urine production lies the nephron, the functional unit of the kidney, where the remarkable process of filtration begins. This article delves into the fascinating journey of the glomerular filtrate, from its initial formation in Bowman's capsule to its ultimate excretion as urine. We'll explore the key players involved, the forces governing filtration, and the subsequent modifications the filtrate undergoes along its path.

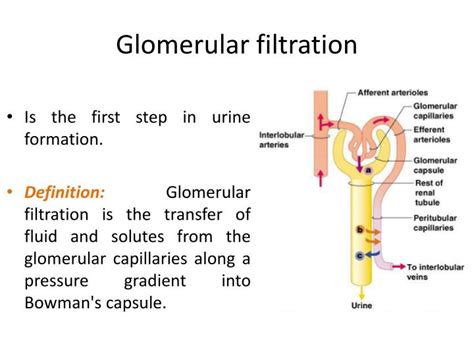

The Glomerulus: The Filtration Powerhouse

The journey begins at the glomerulus, a network of capillaries nestled within Bowman's capsule. This structure is unique because of its high permeability, crucial for the efficient filtration of blood. The glomerular capillaries are fenestrated, meaning they possess numerous pores, allowing for the passage of smaller molecules while retaining larger ones like blood cells and plasma proteins. This initial filtration process is largely passive, driven by the interplay of hydrostatic and oncotic pressures.

Hydrostatic Pressure: The Driving Force

Glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure (PGC) is the primary force driving filtration. This pressure, significantly higher than in other capillary beds, pushes water and dissolved solutes from the glomerular capillaries into Bowman's space. This high pressure is maintained by the afferent arteriole, which has a larger diameter than the efferent arteriole, creating a bottleneck effect and increasing the pressure within the glomerular capillaries.

Oncotic Pressure: The Counterforce

Opposing PGC is the glomerular oncotic pressure (πGC), also known as colloid osmotic pressure. This pressure is exerted by the proteins within the glomerular capillaries, primarily albumin. These proteins attract water, pulling it back into the capillaries and resisting the filtration process. The concentration of these proteins remains relatively high within the glomerular capillaries because large proteins are largely excluded from the filtrate.

Bowman's Capsule Hydrostatic Pressure: The Restraint

Finally, Bowman's capsule hydrostatic pressure (PBS) acts as a counterforce to PGC. This pressure is generated by the fluid already present in Bowman's space. As filtrate accumulates, PBS increases, opposing further filtration.

Net Filtration Pressure: The Decisive Factor

The net filtration pressure (NFP) is the ultimate determinant of filtration rate. It is calculated as:

NFP = PGC - (πGC + PBS)

A healthy NFP ensures a consistent and adequate filtration rate, essential for maintaining homeostasis. Any significant alteration in these pressures, such as increased blood pressure leading to higher PGC, or damage to the glomerular capillaries increasing πGC, can drastically affect the filtration rate and ultimately renal function.

Bowman's Capsule: The Initial Collection Point

Once the filtrate passes through the glomerular capillaries, it enters Bowman's capsule, also known as the glomerular capsule. This cup-shaped structure acts as a collection point for the filtrate, ensuring its smooth passage into the renal tubule. The filtrate at this stage is essentially a protein-free ultrafiltrate of plasma, containing water, glucose, amino acids, electrolytes, and waste products like urea and creatinine. However, it is not yet urine; it will undergo significant modification as it travels through the nephron.

The Renal Tubule: Fine-Tuning the Filtrate

The filtrate's journey continues through the renal tubule, a long, convoluted structure divided into distinct segments: the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT), the loop of Henle, the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), and the collecting duct. Each segment plays a crucial role in modifying the filtrate composition, fine-tuning it into the final urine.

Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT): Reabsorption Central

The PCT is the workhorse of the nephron, responsible for the majority of reabsorption. This process involves the selective movement of essential substances from the filtrate back into the peritubular capillaries. This is largely an active process, requiring energy expenditure.

- Glucose and Amino Acids: These essential nutrients are almost completely reabsorbed in the PCT via secondary active transport, driven by the sodium gradient.

- Electrolytes: Sodium, chloride, potassium, and other ions are actively and passively reabsorbed, maintaining electrolyte balance.

- Water: Water follows the reabsorption of solutes via osmosis.

- Bicarbonate: Crucial for maintaining acid-base balance, bicarbonate is reabsorbed through a complex process involving carbonic anhydrase.

The PCT also plays a role in secretion, actively transporting certain substances from the peritubular capillaries into the filtrate. This includes hydrogen ions (H+), contributing to acid-base regulation, and certain drugs and toxins.

Loop of Henle: Concentrating the Urine

The loop of Henle descends into the renal medulla, a region with a high osmolarity (solute concentration). This creates a concentration gradient that enables the loop to concentrate the urine. The descending limb is permeable to water but relatively impermeable to solutes, allowing water to passively leave the filtrate and enter the medullary interstitium. The ascending limb is impermeable to water but actively transports sodium and chloride ions out of the filtrate, contributing to the medullary concentration gradient. This countercurrent mechanism establishes an osmotic gradient essential for concentrating the urine, conserving water.

Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT): Fine-tuning and Hormonal Regulation

The DCT receives the filtrate from the loop of Henle and plays a crucial role in fine-tuning its composition under hormonal control.

- Aldosterone: This hormone regulates sodium and potassium reabsorption, affecting blood pressure and electrolyte balance.

- Parathyroid Hormone (PTH): PTH stimulates calcium reabsorption, crucial for maintaining calcium homeostasis.

- Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH): ADH influences water reabsorption in the collecting duct, regulating urine concentration.

The DCT also participates in secretion, contributing to the excretion of hydrogen ions and potassium ions.

Collecting Duct: Final Adjustments and Urine Formation

The collecting duct receives filtrate from multiple nephrons and is the final site of modification before urine formation. The permeability of the collecting duct to water is regulated by ADH. In the presence of ADH, the collecting duct becomes highly permeable to water, allowing for significant water reabsorption and the production of concentrated urine. In the absence of ADH, the collecting duct remains impermeable to water, resulting in dilute urine. The collecting duct also plays a role in acid-base balance through the secretion of hydrogen ions and reabsorption of bicarbonate.

From Filtrate to Urine: The Final Product

The fluid that emerges from the collecting duct is now urine, a waste product containing excess water, electrolytes, urea, creatinine, and other metabolic byproducts. The composition of urine is tightly regulated to maintain the body's internal environment. It reflects the body's overall health and can be a valuable diagnostic tool for various diseases and conditions.

Factors Affecting Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

Several factors can influence the GFR, affecting the amount of filtrate produced. These include:

- Blood pressure: Increased blood pressure leads to increased PGC and consequently higher GFR. Conversely, decreased blood pressure lowers GFR.

- Renal blood flow: Reduced blood flow to the kidneys diminishes GFR.

- Afferent and efferent arteriolar tone: Changes in the diameter of these arterioles directly impact PGC.

- Plasma protein concentration: Increased plasma proteins increase πGC, reducing GFR.

- Hormonal influences: Hormones like angiotensin II and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) influence GFR through their effects on vascular tone.

Clinical Significance: Understanding GFR for Disease Diagnosis

The GFR is a crucial indicator of kidney function. A decreased GFR signifies impaired kidney function, a condition known as chronic kidney disease (CKD). Measuring GFR helps clinicians assess the severity of CKD and monitor the progression of the disease. Early detection and management of CKD are vital in preventing further kidney damage and complications. Accurate GFR assessment relies on various methods, including creatinine clearance and specialized equations, offering valuable insights into kidney health.

Conclusion: A Complex and Vital Process

The journey of the glomerular filtrate, from Bowman's capsule to the final urine, is a complex and tightly regulated process. This intricate system maintains homeostasis, ensuring that the body's internal environment remains stable despite fluctuations in the external environment. Understanding the intricacies of this process is vital in comprehending the function of the kidneys and their significance in overall health. Any impairment in any part of this complex system can have profound effects on the body's ability to maintain homeostasis, highlighting the critical importance of maintaining renal health. Further research continuously unravels the complexities of the nephron and its underlying mechanisms, improving our understanding of kidney physiology and disease.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Mass Of Empty Crucible Cover

Mar 27, 2025

-

In The Peptide Ala Try Gly Phe The N Terminal Amino Acid Is

Mar 27, 2025

-

Marathon Runners Can Lose A Great Deal Of Na

Mar 27, 2025

-

Exhibit 12 4 Marginal Tax Rate Lines Quizlet

Mar 27, 2025

-

The Functional Role Of Sporopollenin Is Primarily To

Mar 27, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Filtrate First Passes From The Glomerular Capsule To The . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.