A Continuous Random Variable May Assume

Holbox

Mar 21, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- A Continuous Random Variable May Assume

- Table of Contents

- A Continuous Random Variable May Assume: A Deep Dive into Probability Distributions

- Defining Continuous Random Variables

- The Probability Density Function (PDF)

- Common Continuous Probability Distributions

- 1. Normal (Gaussian) Distribution

- 2. Exponential Distribution

- 3. Uniform Distribution

- 4. Gamma Distribution

- 5. Beta Distribution

- Applications of Continuous Random Variables

- Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts

- Conclusion

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

A Continuous Random Variable May Assume: A Deep Dive into Probability Distributions

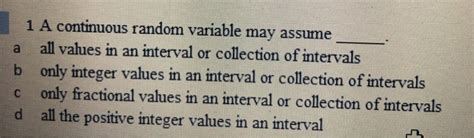

A continuous random variable, unlike its discrete counterpart, can take on any value within a given range or interval. This seemingly simple distinction opens up a vast landscape of possibilities and complexities in probability theory and its applications. Understanding what a continuous random variable may assume involves grasping the underlying probability density functions (PDFs) that govern their behavior. This article will delve into the characteristics, common distributions, and practical applications of continuous random variables.

Defining Continuous Random Variables

A continuous random variable is a variable whose value can be any real number within a given range. This contrasts with discrete random variables, which can only take on specific, distinct values (e.g., the number of heads in three coin flips). The key difference lies in the ability to take on infinitely many values within an interval. Think of measuring height – a person's height isn't restricted to specific values like 5'0", 5'1", etc.; it can be 5'0.5", 5'0.55", and so on, leading to an infinite number of possibilities within a range.

Importantly, the probability of a continuous random variable assuming any single specific value is always zero. This might sound counterintuitive, but consider the infinite possibilities. If you were to assign a non-zero probability to each value, the sum of these probabilities would be infinite, violating the fundamental axiom of probability. Instead, we work with the probability of the variable falling within a specific interval. This probability is given by the integral of the probability density function (PDF) over that interval.

The Probability Density Function (PDF)

The heart of understanding continuous random variables lies in the probability density function (PDF). The PDF, denoted as f(x), describes the relative likelihood of the variable taking on a value around x. It's crucial to remember that f(x) itself is not a probability; instead, the probability of the variable falling within a specific interval [a, b] is given by the integral:

P(a ≤ X ≤ b) = ∫<sub>a</sub><sup>b</sup> f(x) dx

This integral represents the area under the curve of the PDF between points a and b. The total area under the entire PDF curve must always equal 1, reflecting the certainty that the variable will assume some value within its range.

Common Continuous Probability Distributions

Several standard distributions model the behavior of continuous random variables across various applications. Understanding these distributions is crucial for applying probability theory to real-world problems. Here are some prominent examples:

1. Normal (Gaussian) Distribution

The normal distribution, arguably the most important continuous distribution, is characterized by its bell-shaped curve. It's defined by two parameters: the mean (μ) and the standard deviation (σ). The PDF is given by a rather complex formula, but its symmetrical shape and properties make it incredibly useful. Many natural phenomena, like height, weight, and measurement errors, approximately follow a normal distribution. The empirical rule (68-95-99.7 rule) provides convenient approximations for probabilities within specific standard deviations from the mean.

Key Properties:

- Symmetrical: The mean, median, and mode are all equal.

- Bell-shaped: Characterized by a central peak and tapering tails.

- Defined by mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ): These parameters determine the location and spread of the distribution.

2. Exponential Distribution

The exponential distribution models the time between events in a Poisson process, a process where events occur randomly and independently at a constant average rate. Examples include the time until a machine fails, the time between customer arrivals at a store, or the lifespan of a certain electronic component. It's defined by a single parameter, λ (lambda), representing the rate parameter. A higher λ indicates a faster rate of events.

Key Properties:

- Memoryless: The probability of an event occurring in the future is independent of how long it's already been waiting.

- Positively skewed: The tail extends towards higher values.

- Defined by the rate parameter (λ): This determines the average time between events (1/λ).

3. Uniform Distribution

The uniform distribution assigns equal probability to all values within a specified interval [a, b]. This means the PDF is a constant function within the interval, and zero outside it. This distribution is used when all values within a range are equally likely.

Key Properties:

- Constant PDF: The probability density is the same for all values within the interval.

- Symmetrical: If the interval is symmetric around its midpoint, the distribution is symmetrical.

- Defined by the interval [a, b]: This determines the range of possible values.

4. Gamma Distribution

The gamma distribution is a flexible distribution with applications in various fields, often used to model waiting times or the sum of exponential random variables. It has two parameters: shape (k) and scale (θ).

Key Properties:

- Shape parameter (k): Influences the shape of the distribution.

- Scale parameter (θ): Influences the spread of the distribution.

- Can be skewed or symmetrical depending on the parameters.

5. Beta Distribution

The beta distribution is defined on the interval [0, 1] and is often used to model probabilities or proportions. It has two shape parameters, α (alpha) and β (beta).

Key Properties:

- Defined on the interval [0, 1]: Ideal for modeling proportions or probabilities.

- Shape parameters (α and β): These parameters determine the shape of the distribution, ranging from U-shaped to J-shaped and unimodal.

Applications of Continuous Random Variables

Continuous random variables are essential tools in diverse fields:

- Finance: Modeling stock prices, interest rates, and other financial instruments. Many financial models rely heavily on normal and other continuous distributions.

- Engineering: Analyzing system reliability, predicting component failure rates, and assessing risks. The exponential distribution plays a crucial role here.

- Physics: Describing physical phenomena like particle velocities and energy levels.

- Statistics: Inferential statistics, hypothesis testing, and estimation heavily rely on continuous distributions.

- Medicine: Modeling patient survival times, drug effectiveness, and disease prevalence.

- Actuarial Science: Calculating insurance premiums and assessing risks.

Understanding and applying continuous random variables is critical for making informed decisions in these and numerous other domains.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts

The world of continuous random variables extends far beyond the distributions mentioned above. Several advanced concepts are essential for a more comprehensive understanding:

- Joint Distributions: Modeling the relationship between multiple continuous random variables. This involves understanding joint probability density functions.

- Conditional Distributions: Analyzing the probability of one variable given the value of another.

- Transformations of Random Variables: Deriving the distribution of a function of a continuous random variable.

- Central Limit Theorem: This fundamental theorem states that the sum of a large number of independent and identically distributed random variables (regardless of their original distribution) tends toward a normal distribution. This is crucial for statistical inference.

- Simulation: Using computational methods to generate random samples from various continuous distributions, allowing for exploring and analyzing complex scenarios.

Conclusion

Continuous random variables are fundamental to probability and statistics, providing a powerful framework for understanding and modeling a wide range of phenomena. Mastering the concepts of probability density functions, common distributions, and their applications is crucial for anyone working in fields that involve uncertainty and variability. While this article provides a solid foundation, continuous exploration and deeper study of advanced concepts are encouraged to fully appreciate the breadth and depth of this important topic. The ability to accurately model and interpret continuous random variables is a vital skill for success in many fields. From predicting financial markets to designing reliable engineering systems, the tools and techniques described herein are indispensable. Continuous learning and practice will solidify your understanding and empower you to effectively utilize these powerful tools.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

All Of The Following Are Elements Of Military Ethics Except

Mar 28, 2025

-

Museums Are Interested In Buying And Exhibiting Works That

Mar 28, 2025

-

A 20 000 Life Insurance Policy Application Is Completed However

Mar 28, 2025

-

Match The Trend To Its Definition

Mar 28, 2025

-

Use The Pivot Table Command On The Insert Tab

Mar 28, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Continuous Random Variable May Assume . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.