Select The Experiments That Use A Randomized Comparative Design

Holbox

Apr 05, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- Select The Experiments That Use A Randomized Comparative Design

- Table of Contents

- Selecting Experiments that Use a Randomized Comparative Design

- What is a Randomized Comparative Design?

- Examples of Experiments Using Randomized Comparative Designs

- Strengths of Randomized Comparative Designs

- Limitations of Randomized Comparative Designs

- Conclusion

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

Selecting Experiments that Use a Randomized Comparative Design

The randomized comparative design is a cornerstone of experimental research, providing a robust framework for establishing cause-and-effect relationships. It's characterized by the random assignment of participants to different groups, allowing researchers to minimize bias and increase the internal validity of their findings. This article delves into various experiments that effectively utilize this design, exploring their methodologies and the insights they offer. We'll examine examples across diverse fields, highlighting the strengths and limitations of the approach.

What is a Randomized Comparative Design?

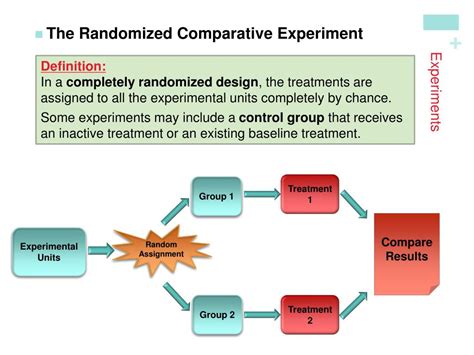

Before diving into specific experiments, let's solidify our understanding of this crucial research design. A randomized comparative design involves comparing the outcomes of at least two groups: a treatment group and a control group (or multiple treatment groups). The key differentiator is the random assignment of participants to these groups. This randomization helps ensure that the groups are comparable at the outset, minimizing the influence of pre-existing differences that could confound the results. This contrasts sharply with observational studies where group assignment is not controlled by the researcher.

Key Features:

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly allocated to different groups, minimizing selection bias.

- Comparison of Groups: The effects of a treatment (intervention, manipulation) are assessed by comparing the outcomes of the treatment group(s) with the control group.

- Control Group: A group that does not receive the treatment, providing a baseline for comparison. This group helps isolate the effect of the treatment.

- Replicable: The clearly defined methods allow other researchers to replicate the study.

Examples of Experiments Using Randomized Comparative Designs

The power of the randomized comparative design is evident across a broad spectrum of disciplines. Here are examples illustrating its diverse applications:

1. Medical Trials: Testing the Efficacy of a New Drug

Consider a clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of a new drug to lower blood pressure. Participants with high blood pressure are randomly assigned to two groups:

- Treatment Group: Receives the new drug.

- Control Group: Receives a placebo (an inactive substance).

After a specified period, researchers compare the blood pressure levels of both groups. If the treatment group shows a significantly greater reduction in blood pressure than the control group, it suggests the drug is effective. The random assignment helps to minimize the possibility that observed differences are due to pre-existing health conditions or other factors rather than the drug itself. This methodology ensures rigorous testing and minimizes bias for reliable results. Proper blinding (masking) of participants and researchers enhances the validity further. Double-blind studies, where neither the participant nor the researcher knows who is receiving the treatment, are considered the gold standard.

2. Educational Research: Evaluating the Impact of a New Teaching Method

In educational settings, this design is frequently used to evaluate the efficacy of new teaching methods. For example, a researcher might want to test a new approach to teaching mathematics. Students are randomly assigned to two classes:

- Treatment Group: Taught using the new method.

- Control Group: Taught using the traditional method.

The researcher then compares the students' performance on standardized math tests at the end of the term. A significant difference in test scores between the groups would provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of the new method. Here, careful consideration of confounding variables like student background and teacher experience is crucial for drawing valid conclusions. Pre-tests can help account for initial differences in student knowledge.

3. Psychology Experiments: Investigating the Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Randomized comparative designs are frequently employed in psychology to assess the impact of different therapeutic interventions. For example, a study might compare the effectiveness of CBT versus a control condition (e.g., a waiting list control) in treating anxiety disorders. Participants are randomly assigned to:

- Treatment Group: Receives CBT.

- Control Group: Placed on a waiting list for treatment, receiving no intervention during the study period.

Researchers then measure anxiety levels using standardized scales before and after the intervention period. A significant reduction in anxiety scores in the CBT group compared to the control group would indicate the therapy's effectiveness. Here, careful assessment of symptoms and the use of standardized measures are critical for ensuring the reliability and validity of the findings. Ethical considerations are paramount in such studies, ensuring that participants in the control group receive appropriate care once the study is completed.

4. Agricultural Science: Comparing the Yields of Different Fertilizers

In agriculture, randomized comparative designs are used extensively to evaluate the effects of different treatments, such as fertilizers or pesticides, on crop yields. For instance, a researcher might compare the yield of corn grown using three different fertilizers:

- Group 1: Fertilizer A

- Group 2: Fertilizer B

- Group 3: Fertilizer C (Control - No fertilizer)

Plots of land are randomly assigned to receive one of the three fertilizers. After the growing season, the corn yield from each plot is measured and compared. Statistical analysis then determines if there are significant differences in yield among the groups, indicating the superiority of one fertilizer over others. The random assignment of plots helps to control for extraneous factors such as soil quality variations across the experimental field.

5. Marketing Research: Testing the Effectiveness of Different Advertising Campaigns

In marketing, A/B testing utilizes a randomized comparative design. Two versions of an advertisement (A and B) are shown to different groups of potential customers:

- Group A: Sees advertisement A.

- Group B: Sees advertisement B.

Researchers then track the responses, such as click-through rates or sales conversions, for each group. A significant difference in response rates indicates which advertisement is more effective. This enables marketers to optimize their campaigns based on empirical evidence. Data analytics play a vital role in this type of experiment. Careful tracking and analysis of metrics are essential for making sound conclusions.

Strengths of Randomized Comparative Designs

- High Internal Validity: Random assignment minimizes the risk of confounding variables, leading to stronger causal inferences.

- Reduced Bias: Randomization helps to mitigate selection bias, a common problem in observational studies.

- Statistical Power: The ability to detect a true effect (if it exists) is increased by having clearly defined and randomly assigned groups.

- Replicability: Clearly defined procedures facilitate replication by other researchers, strengthening the reliability of findings.

- Generalizability (with caveats): If the sample is representative of the population of interest, results can often be generalized to a larger population.

Limitations of Randomized Comparative Designs

- Artificiality: The controlled environment of experiments may not perfectly reflect real-world conditions, limiting the external validity (generalizability) of findings.

- Ethical Considerations: In some cases, withholding a potentially beneficial treatment from the control group might raise ethical concerns.

- Practical Challenges: Randomizing participants can be difficult and time-consuming, particularly with large samples or diverse populations.

- Cost: Conducting experiments, especially those involving large samples, can be expensive.

- Sample Size: Insufficient sample size can reduce statistical power, increasing the risk of Type II error (failing to detect a real effect).

Conclusion

The randomized comparative design remains a powerful tool for investigating cause-and-effect relationships across numerous fields. Its strength lies in its ability to minimize bias and establish causal inferences. While limitations exist, careful planning, execution, and analysis can mitigate these shortcomings. Understanding the design's strengths and weaknesses is crucial for researchers to effectively select and implement this critical methodology, ensuring the generation of robust and meaningful scientific findings. The examples outlined above illustrate the broad scope of its applications and its continuing importance in advancing knowledge across diverse disciplines. Future research will continue to refine and expand the applications of this invaluable design, furthering our understanding of the world around us.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Presence Or Growth Of Microorganisms Is A Type Of

Apr 12, 2025

-

Which Statement About Dna Replication Is Correct

Apr 12, 2025

-

What Is The Mean Of Sample Means

Apr 12, 2025

-

For Each Graph Below State Whether It Represents A Function

Apr 12, 2025

-

The Bootstrap Program Executes Which Of The Following

Apr 12, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Select The Experiments That Use A Randomized Comparative Design . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.