Label The Structures Of The Joint

Holbox

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Labeling the Structures of a Joint: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding the intricate structures of a joint is fundamental to comprehending human movement, biomechanics, and the origins of musculoskeletal disorders. This comprehensive guide will delve into the various components of a joint, providing detailed descriptions and visual aids to aid in proper labeling. We'll explore different joint classifications and highlight the key anatomical features that distinguish them. This in-depth analysis will equip you with the knowledge needed to accurately label and understand the complex mechanics of these crucial body parts.

Types of Joints and Their Structures

Joints, or articulations, are where two or more bones meet. Their classification hinges on the type of connective tissue binding them and the degree of movement allowed. The three main types are fibrous, cartilaginous, and synovial.

1. Fibrous Joints: Immovable Connections

Fibrous joints are characterized by a lack of a joint cavity and are connected by fibrous connective tissue. Movement is minimal or nonexistent. Examples include:

-

Sutures: Found only in the skull, these joints are tightly interlocked, forming strong, immovable connections. Labeling key features: The serrated edges of the bones interdigitating, the dense fibrous connective tissue filling the spaces between the bones.

-

Syndesmoses: Bones are connected by a ligament or a membrane. A slight degree of movement might be permitted. Labeling key features: The ligament connecting the bones, the fibrous tissue between the bones, the relative distance between bones depending on the flexibility of the connecting tissue. The distal tibiofibular joint is a classic example.

-

Gomphoses: These unique joints anchor teeth to the sockets of the maxilla and mandible. Labeling key features: The periodontal ligament securing the tooth root, the alveolar bone of the jaw, the cementum covering the tooth root.

2. Cartilaginous Joints: Slightly Movable Articulations

Cartilaginous joints feature a connection made of cartilage. They allow for limited movement. Two subtypes exist:

-

Synchondroses: Bones are united by hyaline cartilage. These are typically temporary joints, eventually ossifying (becoming bone) during growth. Labeling key features: The hyaline cartilage layer uniting the bones, the epiphyseal plates (growth plates) in long bones being prime examples.

-

Symphyses: Bones are connected by fibrocartilage, offering more resilience and flexibility than synchondroses. The intervertebral discs between vertebrae are excellent examples. Labeling key features: The fibrocartilage pad, the bony components (vertebral bodies) on either side, the annulus fibrosus (outer layer of the disc), and the nucleus pulposus (inner, gelatinous part of the disc).

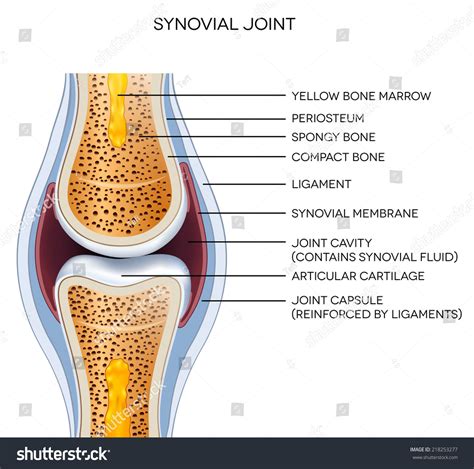

3. Synovial Joints: Freely Movable Articulations

Synovial joints are the most common type, characterized by a synovial cavity filled with synovial fluid. This fluid lubricates the joint and reduces friction during movement. These joints are highly mobile. Let's explore the key structural components requiring labeling:

Key Structures of a Synovial Joint:

-

Articular Cartilage: A layer of hyaline cartilage covering the articulating surfaces of the bones. Labeling focus: Its smooth, glassy appearance, its role in reducing friction, and its location on the bone ends.

-

Articular Capsule: A fibrous sac encasing the joint, composed of an outer fibrous layer and an inner synovial membrane. Labeling focus: Distinguishing the fibrous capsule (providing stability) from the synovial membrane (secreting synovial fluid).

-

Synovial Membrane: Lines the inner surface of the articular capsule, producing the viscous synovial fluid. Labeling focus: Its location within the joint cavity, its role in lubrication and nutrition of the articular cartilage.

-

Synovial Fluid: A lubricating fluid within the joint cavity, reducing friction and providing nourishment to the articular cartilage. Labeling focus: Its location within the joint cavity, its viscous nature.

-

Joint Cavity: The space enclosed by the articular capsule, containing the synovial fluid. Labeling focus: Its location within the joint and its role in allowing movement.

-

Ligaments: Strong, fibrous bands of connective tissue connecting bones, providing stability and limiting excessive movement. Labeling focus: Their attachments to specific bony landmarks, their orientation relative to the joint, and their role in joint stability.

-

Accessory Structures (Variable): Several structures enhance the functionality and protection of certain synovial joints. These may include:

-

Menisci: Fibrocartilaginous pads found in some joints (e.g., knee) that act as shock absorbers and improve congruency between articulating surfaces. Labeling focus: Their shape, location within the joint, and their role in shock absorption and joint stability.

-

Bursae: Fluid-filled sacs located between tendons, ligaments, and bones that reduce friction. Labeling focus: Their location relative to the joint, their fluid-filled nature.

-

Tendons: Connect muscles to bones, transmitting the force of muscle contraction to produce movement. Labeling focus: Their attachments to muscle and bone, their role in movement.

-

Classifying Synovial Joints by Movement

Synovial joints are further classified based on the type of movement they allow:

1. Uniaxial Joints: Movement in One Plane

-

Hinge Joints: Allow movement in one plane (flexion and extension). Examples include the elbow and knee. Labeling focus: The hinge-like articulation, the range of motion restricted to a single axis.

-

Pivot Joints: Allow rotation around a single axis. The atlantoaxial joint (between the first two cervical vertebrae) is a prime example. Labeling focus: The rotational movement, the axis of rotation.

2. Biaxial Joints: Movement in Two Planes

-

Condyloid Joints: Allow movement in two planes (flexion/extension and abduction/adduction). The metacarpophalangeal joints (knuckles) are classic examples. Labeling focus: The oval-shaped articular surfaces, the two axes of movement.

-

Saddle Joints: Allow movement in two planes, similar to condyloid joints, but with a greater range of motion. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb is a unique example. Labeling focus: The saddle-shaped articular surfaces, the wide range of movement in two planes.

3. Multiaxial Joints: Movement in Multiple Planes

-

Ball-and-Socket Joints: Allow movement in all three planes (flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and rotation). The shoulder and hip joints are prime examples. Labeling focus: The spherical head of one bone fitting into the concave socket of another bone, the three axes of rotation.

-

Plane Joints: Allow gliding or sliding movements between flat articular surfaces. The intercarpal and intertarsal joints are good examples. Labeling focus: The flat articular surfaces, the limited range of gliding motion.

Practical Applications: Labeling Exercises

To solidify your understanding, practice labeling joint structures using anatomical diagrams or models. Focus on:

- Identifying the joint type: Determine if it's fibrous, cartilaginous, or synovial.

- Identifying key structures: Locate and label the articular cartilage, articular capsule, synovial membrane, synovial fluid, ligaments, and any accessory structures (menisci, bursae, tendons).

- Describing joint movement: Based on the joint type and structure, describe the range of motion permitted.

Regular practice will improve your ability to accurately label and understand the complex anatomy of joints. Using anatomical atlases, online resources, and three-dimensional models can greatly enhance your learning experience.

Clinical Significance: Understanding Joint Disorders

Understanding joint structures is paramount in diagnosing and treating musculoskeletal disorders. Conditions like osteoarthritis (degeneration of articular cartilage), rheumatoid arthritis (inflammation of the synovial membrane), and ligament sprains directly impact the joint's integrity and function. Accurate labeling of affected structures facilitates clear communication between healthcare professionals and contributes to effective treatment planning.

Conclusion: Mastering Joint Anatomy

The ability to accurately label the structures of a joint is a critical skill for anyone studying anatomy, biomechanics, or related fields. This comprehensive guide has provided a detailed overview of joint classifications, key structural components, and clinical applications. By combining theoretical knowledge with practical labeling exercises, you can build a strong foundation in understanding the fascinating complexity of human joints. Remember, consistent practice and engagement with diverse learning resources are vital to mastering this crucial aspect of human anatomy. Continue exploring different joint types and their unique characteristics to deepen your understanding.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

A Patient Has Arrived Late To Her Physical Therapy Appointment

Mar 21, 2025

-

Reasons To Study Operations Management Include

Mar 21, 2025

-

A Disadvantage Of Global Teams For Product Design Is That

Mar 21, 2025

-

Use The Figure Below To Answer The Following Question

Mar 21, 2025

-

Stockholders Have The Right To At Stockholders Meetings

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Label The Structures Of The Joint . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.