Exercise 12.7 Putting It All Together To Decipher Earth History

Holbox

Mar 20, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

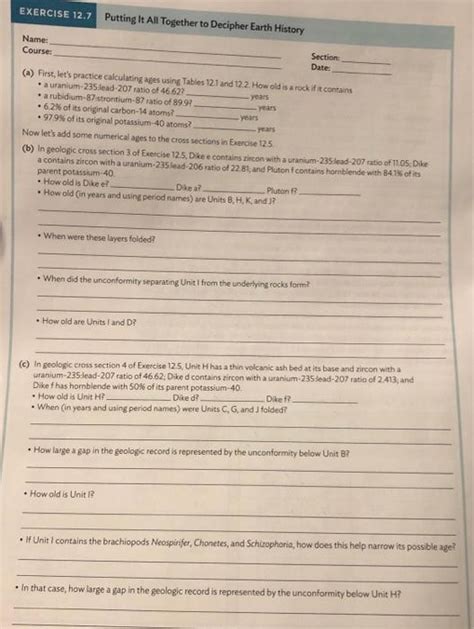

Exercise 12.7: Putting It All Together to Decipher Earth History

This exercise focuses on synthesizing various geological techniques and principles to interpret Earth's history. It's a culmination of knowledge gained throughout a geology course, requiring students to integrate stratigraphy, paleontology, geochronology, structural geology, and geomorphology to reconstruct a geological narrative. We'll explore this comprehensive approach, examining the key steps and considerations involved in deciphering Earth's history from geological evidence.

1. Assembling the Evidence: Data Acquisition and Integration

The foundation of any geological interpretation lies in the meticulous collection and analysis of data. This involves:

1.1 Field Observations: The Foundation of Geological Understanding

- Stratigraphic Relationships: Detailed field mapping is crucial to understand the sequence of rock layers (strata). This includes identifying bedding planes, unconformities (breaks in the rock record), faults, and folds. Careful observation of rock types, their thicknesses, and lateral variations is paramount. The principle of superposition (older rocks are at the bottom, unless deformed) guides the relative age determination.

- Paleontological Evidence: Fossils provide invaluable insights into past life and environments. Identifying and classifying fossils allows for biostratigraphic correlation – matching rock layers based on their fossil content. Index fossils, with short stratigraphic ranges and wide geographic distribution, are particularly useful for correlation.

- Structural Geology: Features like folds, faults, and joints reveal the tectonic history of a region. Analyzing their orientations, magnitudes, and relationships with other geological structures provides clues about past deformation events. Understanding stress regimes and their impact on rock formations is crucial.

- Geomorphological Features: Landforms, such as river valleys, mountains, and coastal features, reflect erosion and depositional processes. Interpreting their origins helps to reconstruct past landscapes and climate conditions. Analyzing drainage patterns, sediment transport, and landform evolution offers valuable insights into the dynamic interplay of geological processes.

1.2 Laboratory Analyses: Enhancing Field Observations

Field observations provide the initial context, but laboratory analyses are necessary to refine and quantify our understanding:

- Petrographic Analysis: Microscopic examination of thin sections of rocks reveals mineral composition, texture, and grain size, helping identify rock types and their origins. This is crucial for understanding sedimentary environments, igneous processes, and metamorphic transformations.

- Geochemical Analysis: Analyzing the chemical composition of rocks and minerals provides information about their formation environments, alteration processes, and ages. Isotope geochemistry, especially radiometric dating, is central to determining absolute ages of rocks and events.

- Paleomagnetic Studies: Analyzing the magnetic properties of rocks can reveal their past magnetic orientations, providing information about plate movements and past magnetic field reversals. This adds another dimension to understanding the temporal context of geological events.

2. Constructing the Narrative: Interpreting the Geological Record

After data acquisition, the next stage is to integrate the observations and analyses to create a cohesive geological narrative. This involves:

2.1 Relative Dating: Establishing Chronological Order

Relative dating techniques, based on principles like superposition, cross-cutting relationships, and faunal succession, are used to establish the chronological sequence of geological events without assigning numerical ages. Unconformities are carefully considered as they represent significant gaps in the geological record, reflecting periods of erosion or non-deposition. Careful correlation of stratigraphic units across different locations is crucial to building a regional geological framework.

2.2 Absolute Dating: Assigning Numerical Ages

Absolute dating, primarily through radiometric methods (like U-Pb, K-Ar, Rb-Sr), provides numerical ages to geological events. These techniques are based on the radioactive decay of isotopes, allowing for precise age determination of rocks and minerals. Combining relative and absolute dating techniques provides a comprehensive chronological framework for interpreting the geological history.

2.3 Reconstructing Paleoenvironments: Understanding Past Conditions

The geological record contains clues about past environments. Sedimentary structures, fossil assemblages, and geochemical signatures can be used to reconstruct paleoenvironments, including:

- Sedimentary Environments: Identifying the depositional environment (e.g., marine, fluvial, glacial) of sedimentary rocks is crucial. This involves analyzing sedimentary structures, grain size, fossil content, and geochemical indicators.

- Paleoclimates: Geological data provides evidence of past climates. This includes oxygen isotope analysis of fossils and sediments, glacial deposits, and the distribution of climate-sensitive organisms.

- Paleogeography: Reconstructing the geographical arrangement of continents and oceans through time is essential. This relies on paleomagnetic data, plate tectonic reconstructions, and the distribution of fossils and rock formations.

3. Integrating Multiple Lines of Evidence: A Holistic Approach

Deciphering Earth's history is not a single-discipline endeavor. It requires integrating multiple lines of evidence to create a coherent and robust interpretation. This involves:

3.1 Cross-Validation: Comparing and Contrasting Data

Different geological techniques provide complementary information. Cross-validation involves comparing and contrasting results from various methods to ensure consistency and identify potential discrepancies. This iterative process refines the interpretation and strengthens the conclusions.

3.2 Addressing Uncertainties: Acknowledging Limitations

Geological interpretations are always subject to uncertainties. It's crucial to acknowledge these limitations and quantify the uncertainties associated with the data and interpretations. This transparent approach builds credibility and fosters further investigation.

3.3 Building a Comprehensive Model: Synthesizing Information

The final goal is to synthesize all the available data into a comprehensive geological model. This model should explain the observed geological features, their relationships, and their chronological sequence. It provides a framework for understanding the evolution of the region and its place within a larger geological context. This model should be presented clearly and concisely, often using diagrams, cross-sections, and maps to communicate the information effectively. It should also incorporate discussions of the uncertainties and limitations of the interpretation.

4. Example: Deciphering the Geological History of a Hypothetical Region

Let's consider a hypothetical region with the following geological observations:

- Lowermost layer: A thick sequence of metamorphic rocks, including gneiss and schist, showing evidence of intense deformation and high-grade metamorphism. Radiometric dating yields ages of approximately 1.8 billion years.

- Overlying layer: A sequence of sedimentary rocks, including conglomerates, sandstones, and shales, showing evidence of fluvial deposition. These rocks contain fossils of early life forms, indicating a Proterozoic age.

- Intermediate layer: An unconformity is observed, representing a significant period of erosion and non-deposition.

- Uppermost layer: A sequence of basalt flows, indicative of volcanic activity. Radiometric dating suggests an age of around 500 million years. These flows are intruded by a granite batholith, dated at 480 million years. The region also shows evidence of faulting and folding, indicating tectonic activity.

Based on these observations, we can construct a geological narrative:

- 1.8 billion years ago: A period of intense mountain building and metamorphism resulted in the formation of the gneiss and schist.

- Proterozoic Era: The mountains were eroded, and fluvial deposition laid down the sedimentary sequence. Early life forms thrived in this environment.

- Significant Unconformity: A long period of erosion removed a considerable thickness of rock, representing a significant gap in the geological record. This could have been due to uplift and erosion, potentially linked to tectonic activity.

- 500 million years ago: Volcanic activity resulted in the basalt flows. Subsequently, a granite batholith intruded the sequence.

- Post-500 million years: Tectonic activity caused faulting and folding of the rock layers.

This interpretation is a simplified example; a real-world analysis would require a much more comprehensive dataset and more sophisticated interpretations. Nevertheless, it demonstrates the process of integrating different lines of evidence to construct a geological history.

5. Conclusion: The Power of Synthesis in Earth Science

Exercise 12.7 highlights the importance of integrating multiple geological techniques and principles to decipher Earth’s history. This holistic approach, combining fieldwork, laboratory analyses, and robust interpretations, allows for a comprehensive understanding of geological processes, past environments, and the evolution of our planet. The ability to synthesize information from diverse sources is a crucial skill for any geologist, enabling them to unravel the complex story etched in the rocks. This detailed analysis demonstrates how seemingly disparate data points, when considered collectively and meticulously, can unveil the intricate tapestry of Earth’s fascinating history. The iterative process of data gathering, analysis, interpretation, and cross-validation ensures a robust and reliable understanding of our planet's past, informing present-day understanding and future predictions. The ability to communicate this understanding effectively, using visual aids and clear narratives, is equally crucial in disseminating knowledge and furthering geological research.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Is Not An Example Of Pii

Mar 20, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Rational Functions Is Graphed Below

Mar 20, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Are Not Research Data

Mar 20, 2025

-

Behaviorism Focuses On Making Psychology An Objective Science By

Mar 20, 2025

-

Setting Up A Unit Conversion Aleks

Mar 20, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Exercise 12.7 Putting It All Together To Decipher Earth History . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.