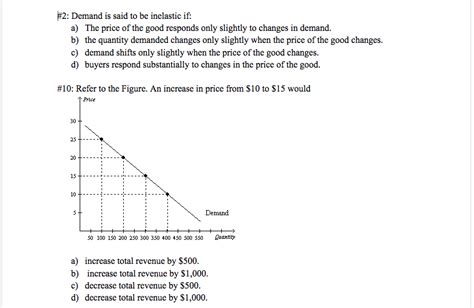

Demand Is Said To Be Inelastic If

Holbox

Mar 30, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

- Demand Is Said To Be Inelastic If

- Table of Contents

- Demand is Said to Be Inelastic If… Understanding Price Sensitivity and Its Implications

- What is Inelastic Demand?

- Key Characteristics of Inelastic Demand:

- Causes of Inelastic Demand:

- 1. Lack of Close Substitutes:

- 2. Necessity versus Luxury:

- 3. Proportion of Income:

- 4. Time Horizon:

- 5. Brand Loyalty and Habit:

- 6. Addictive Goods:

- Implications of Inelastic Demand:

- 1. Businesses and Pricing Strategies:

- 2. Government Policy:

- 3. Consumer Behavior:

- Examples of Inelastic Demand in Real-World Markets:

- Inelastic Demand and Market Equilibrium:

- Measuring Inelasticity: Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

- Conclusion: Navigating the Implications of Inelastic Demand

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

Demand is Said to Be Inelastic If… Understanding Price Sensitivity and Its Implications

Demand elasticity is a fundamental concept in economics that measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to changes in price. Understanding this concept is crucial for businesses making pricing decisions, governments implementing policies, and individuals making purchasing choices. This article delves deep into the concept of inelastic demand, exploring its characteristics, causes, implications, and real-world examples. We'll uncover when demand is considered inelastic and what factors contribute to this important economic phenomenon.

What is Inelastic Demand?

Demand is said to be inelastic if a percentage change in price leads to a smaller percentage change in quantity demanded. In simpler terms, even if the price increases significantly, the quantity demanded doesn't decrease proportionally. This means consumers are relatively insensitive to price changes for these goods or services. The price elasticity of demand (PED) in this case is between 0 and -1. A PED of -0.5, for example, indicates that a 10% increase in price would lead to only a 5% decrease in quantity demanded. A PED of 0 indicates perfectly inelastic demand, where quantity demanded remains unchanged regardless of price fluctuations.

Key Characteristics of Inelastic Demand:

- Steep Demand Curve: Graphically, inelastic demand is represented by a steep demand curve. This visual representation clearly shows that even with substantial price changes, the quantity demanded changes only slightly.

- Limited Substitutes: Goods and services with inelastic demand typically have few or no close substitutes. Consumers find it difficult to switch to alternatives, making them less sensitive to price increases.

- Necessity Goods: Many inelastic goods are necessities – things people need regardless of price. Examples include essential medicines, gasoline, and electricity.

- Small Proportion of Income: Goods representing a small portion of a consumer's income tend to have inelastic demand. A small price increase on a low-cost item may not significantly impact a consumer's budget.

- Brand Loyalty: Strong brand loyalty can also contribute to inelastic demand. Consumers may be willing to pay a premium for a specific brand, even if similar alternatives exist at lower prices.

- Urgency: Time sensitivity plays a role. If a good or service is urgently needed, the demand is likely to be inelastic, as consumers will pay higher prices to obtain it immediately. This applies to emergency medical services, for example.

Causes of Inelastic Demand:

Several factors contribute to the inelasticity of demand for a particular good or service. Understanding these factors is crucial for businesses to effectively manage their pricing strategies.

1. Lack of Close Substitutes:

The absence of easily available and affordable substitutes is a primary driver of inelastic demand. If a consumer needs a specific product and there are no satisfactory alternatives, they are more likely to accept price increases without significantly reducing their consumption. Consider prescription drugs; the lack of substitutes for a specific medication often leads to inelastic demand.

2. Necessity versus Luxury:

Necessity goods, items considered essential for daily life, exhibit inelastic demand. Consumers view these goods as non-discretionary and continue purchasing them even when prices rise. Examples include food, water, and shelter. Luxury goods, on the other hand, tend to have elastic demand, as consumers are more sensitive to price changes for non-essential items.

3. Proportion of Income:

The proportion of a consumer's income spent on a particular good also influences demand elasticity. If a good represents a small percentage of income, a price increase may have a minimal impact on the consumer's budget, resulting in inelastic demand. Conversely, if a good accounts for a substantial portion of income, consumers are more likely to reduce consumption in response to a price increase.

4. Time Horizon:

The time horizon considered also matters. In the short term, demand for many goods tends to be inelastic because consumers may not have time to adjust their consumption patterns. However, in the long term, consumers may find substitutes or change their habits, leading to more elastic demand.

5. Brand Loyalty and Habit:

Strong brand loyalty or ingrained habits can create inelastic demand. Consumers may be reluctant to switch to alternative brands, even if the price difference is significant, because of familiarity, trust, or perceived quality differences.

6. Addictive Goods:

Addictive goods and services, such as cigarettes or certain drugs, exhibit highly inelastic demand because consumers are physiologically or psychologically dependent on them. Price increases tend to have a minimal impact on the quantity demanded.

Implications of Inelastic Demand:

Understanding inelastic demand has significant implications for various stakeholders:

1. Businesses and Pricing Strategies:

Businesses selling goods with inelastic demand can potentially increase their revenue by raising prices. However, this strategy must be implemented cautiously, considering factors such as competition and the potential for long-term negative impacts on brand loyalty. Raising prices too drastically can eventually lead to a decline in sales volume.

2. Government Policy:

Governments often use taxes on goods with inelastic demand to increase revenue. Since demand is relatively insensitive to price increases, taxes can generate substantial revenue without significantly reducing consumption. Sin taxes on cigarettes and alcohol are examples of this strategy. However, such policies can also raise ethical concerns about disproportionately impacting low-income groups.

3. Consumer Behavior:

Consumers with inelastic demand are less influenced by price changes. This can lead to situations where consumers continue to purchase necessary goods or services even if the price increases significantly, impacting their budgets.

Examples of Inelastic Demand in Real-World Markets:

Numerous examples illustrate the concept of inelastic demand across various sectors.

-

Gasoline: Especially in the short term, gasoline demand is often inelastic. People need to commute to work, and alternatives are not always readily available or affordable. A price increase might lead to a slight reduction in driving, but not a significant decrease in gasoline consumption.

-

Prescription Drugs: Essential medications often have inelastic demand. Consumers are unlikely to reduce their consumption of life-saving drugs, even if prices increase substantially.

-

Salt: A basic necessity, salt demonstrates high inelasticity. Consumers need salt for cooking and preservation, and there are few suitable substitutes. Even large price increases are unlikely to dramatically change consumption.

-

Electricity: In many regions, electricity is a necessity for daily life and work. While consumers might try to conserve energy, the reduction in consumption due to price hikes is usually minimal in the short term.

-

Cigarettes: Cigarettes are a prime example of an addictive good with inelastic demand. Smokers often continue purchasing cigarettes, regardless of price increases, driven by nicotine addiction.

Inelastic Demand and Market Equilibrium:

In a free market, the equilibrium price and quantity are determined by the intersection of the supply and demand curves. With inelastic demand, a shift in supply can lead to significant price changes with relatively small changes in quantity demanded. For example, a decrease in supply (e.g., due to a natural disaster affecting production) would lead to a sharp price increase with only a small reduction in quantity demanded. This can lead to significant revenue gains for suppliers.

Measuring Inelasticity: Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

The price elasticity of demand (PED) is a numerical measure of how responsive quantity demanded is to a change in price. It's calculated as:

PED = (% Change in Quantity Demanded) / (% Change in Price)

Inelastic demand is characterized by a PED value between 0 and -1. A PED of -0.5, for instance, implies that a 10% price increase leads to only a 5% decrease in quantity demanded. A PED of -1 indicates unitary elastic demand, where the percentage changes are equal. A PED of less than -1 represents elastic demand, indicating that quantity demanded is more sensitive to price changes.

Conclusion: Navigating the Implications of Inelastic Demand

Understanding the concept of inelastic demand is essential for businesses, policymakers, and consumers alike. The relative insensitivity of quantity demanded to price changes has significant implications for pricing strategies, tax policies, and individual purchasing decisions. By recognizing the factors that contribute to inelastic demand – such as the lack of substitutes, necessity, and brand loyalty – stakeholders can make informed decisions about resource allocation, pricing policies, and consumption patterns. While businesses can leverage inelastic demand to generate higher revenue, they must remain mindful of the potential risks associated with excessive price increases and the long-term impact on consumer behavior and brand loyalty. The ethical considerations surrounding policies that exploit inelastic demand, particularly for essential goods and services, also need careful consideration. The accurate measurement of PED through thorough market research is vital for effective strategic planning in any situation influenced by price sensitivity.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Term Segregation Is Defined In The Text As

Apr 02, 2025

-

Suffering Should Be Faced Joyfully For The Christian Because

Apr 02, 2025

-

Which Best Describes The Fossil Record

Apr 02, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Statements Is Accurate About Standard Precautions

Apr 02, 2025

-

You Are Responsible For Which Of The Following

Apr 02, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Demand Is Said To Be Inelastic If . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.