According To The Cognitive View Of Classical Conditioning

Holbox

Mar 27, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

- According To The Cognitive View Of Classical Conditioning

- Table of Contents

- According to the Cognitive View of Classical Conditioning

- The Traditional Behavioral Account: Stimulus-Response Connections

- The Cognitive Revolution: Introducing Mental Processes

- Key Principles of the Cognitive View of Classical Conditioning

- 1. Contingency and Predictability: More Than Just Association

- 2. The Role of Attention and Expectancy: Active Processing, Not Passive Association

- 3. Cognitive Maps and Representations: Internal Models of the World

- 4. The Importance of Higher-Order Conditioning: Building on Existing Knowledge

- Contrasting the Cognitive and Behavioral Views

- Implications and Applications of the Cognitive View

- Further Research and Future Directions

- Conclusion

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

According to the Cognitive View of Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning, a cornerstone of learning theory, traditionally emphasizes the formation of automatic stimulus-response associations. However, the cognitive view challenges this purely mechanistic perspective, arguing that mental processes play a crucial role in the learning process. This article delves into the cognitive view of classical conditioning, exploring its key principles, contrasting it with the traditional behavioral account, and examining its implications for our understanding of learning and behavior.

The Traditional Behavioral Account: Stimulus-Response Connections

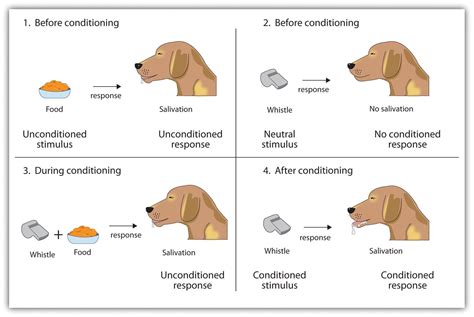

Before diving into the cognitive perspective, it's crucial to understand the traditional, behaviorist viewpoint on classical conditioning, primarily shaped by Ivan Pavlov's experiments with dogs. Pavlov demonstrated that a neutral stimulus (e.g., a bell), repeatedly paired with an unconditioned stimulus (UCS, e.g., food) that elicits an unconditioned response (UCR, e.g., salivation), eventually becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS). After repeated pairings, the CS alone elicits a conditioned response (CR), similar to the UCR. This is the essence of classical conditioning – the formation of an automatic association between the CS and the UCS, leading to the CR.

The behaviorist approach emphasizes the predictability of the UCS. The strength of the CR is directly related to the reliability with which the CS predicts the UCS. If the CS is consistently followed by the UCS, the CR will be strong. If the CS is sometimes followed by the UCS and sometimes not, the CR will be weaker or even extinguished. This focus on observable behaviors and the avoidance of internal mental states is a defining feature of behaviorism.

The Cognitive Revolution: Introducing Mental Processes

The cognitive revolution in psychology challenged the purely stimulus-response framework of behaviorism. Cognitive psychologists argued that learning isn't just about forming simple associations; it involves complex mental processes, including attention, expectation, and conscious awareness. This shift significantly altered our understanding of classical conditioning, giving rise to the cognitive view.

Key Principles of the Cognitive View of Classical Conditioning

The cognitive view of classical conditioning proposes that animals and humans aren't simply passive recipients of stimuli but actively process information about their environment. Several key principles highlight this perspective:

1. Contingency and Predictability: More Than Just Association

While behaviorists emphasize the association between CS and UCS, the cognitive view highlights the importance of contingency – the statistical relationship between the CS and UCS. It's not just about pairing; it's about whether the CS reliably predicts the UCS. Animals actively assess this relationship, learning to anticipate the UCS based on the presence or absence of the CS. Experiments showing that blocking and overshadowing effects occur demonstrate this—learning is influenced not only by contiguity (the proximity of CS and UCS in time) but also by the animal's evaluation of predictive value.

For instance, if a light (CS1) consistently predicts a shock (UCS), but a tone (CS2) is added but doesn't add predictive information (the shock still occurs regardless of the tone), the animal will learn to fear the light but not the tone. This is blocking, demonstrating that simple contiguity isn't enough; predictive value is essential.

2. The Role of Attention and Expectancy: Active Processing, Not Passive Association

Cognitive theories emphasize the role of attention and expectancy in classical conditioning. Animals are selective in what they attend to; only stimuli that are salient or relevant to their needs will be processed thoroughly. This selectivity explains why some stimuli become conditioned stimuli more readily than others. Furthermore, animals form expectancies about the likely occurrence of the UCS based on their past experiences with the CS. These expectancies influence the strength and nature of the CR. If an animal expects a UCS, the CR will be stronger than if it doesn't. This contrasts with the behaviorist view, which minimizes the role of conscious awareness and anticipation.

3. Cognitive Maps and Representations: Internal Models of the World

Cognitive theories propose that animals develop internal representations or cognitive maps of their environment. These mental models allow them to predict events and adjust their behavior accordingly. In the context of classical conditioning, animals don't simply form associations between stimuli; they build representations that incorporate the relationships between stimuli and outcomes. This understanding facilitates flexible and adaptive responses to changes in the environment, unlike the rigid, automatic responses implied by behaviorism.

4. The Importance of Higher-Order Conditioning: Building on Existing Knowledge

Higher-order conditioning demonstrates the cognitive flexibility of learning. Once a CS is established, it can be used to condition a new stimulus. For instance, if a light (CS1) predicts food (UCS), then pairing a tone (CS2) with the light can eventually lead to the tone eliciting a CR (salivation), even though the tone was never directly paired with the food. This highlights the animal's capacity to build upon existing knowledge and create complex associative networks, rather than simply forming isolated stimulus-response links.

Contrasting the Cognitive and Behavioral Views

The key difference between the cognitive and behavioral views lies in their emphasis on internal mental processes. The behavioral view focuses on observable behaviors and simple stimulus-response associations, neglecting the role of internal representations, attention, and expectancy. The cognitive view, in contrast, integrates these mental processes into its explanation of classical conditioning, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the learning process.

| Feature | Behavioral View | Cognitive View |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Observable behaviors, S-R associations | Internal mental processes, information processing |

| Mechanism | Stimulus-response pairings | Contingency, predictability, attention, expectancy |

| Role of animal | Passive recipient of stimuli | Active processor of information |

| Representation | No internal representation | Internal representations, cognitive maps |

| Learning | Automatic, reflexive | Flexible, adaptive |

Implications and Applications of the Cognitive View

The cognitive view of classical conditioning has significant implications for various fields:

-

Therapy: Understanding the cognitive aspects of conditioning is crucial for developing effective therapies for phobias and anxieties. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) incorporates principles from both cognitive and behavioral perspectives, addressing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

-

Education: Applying cognitive principles to educational settings can improve learning outcomes. By understanding how students process information and form expectations, educators can design more effective teaching strategies.

-

Marketing and Advertising: Understanding how consumers process information and form associations between products and positive emotions is crucial for successful marketing campaigns. Classical conditioning principles, viewed through a cognitive lens, inform strategies aimed at creating brand loyalty and positive associations with products.

-

Animal training: The cognitive view provides a more nuanced understanding of animal learning, allowing for more effective and humane training methods that consider the animal's mental state and cognitive abilities.

Further Research and Future Directions

While the cognitive view has significantly advanced our understanding of classical conditioning, several areas warrant further investigation:

-

The neural mechanisms: Future research should explore the neural substrates underlying cognitive processes in classical conditioning, connecting the mental processes with specific brain regions and neurotransmitters.

-

Individual differences: Exploring the individual differences in attention, memory, and cognitive processing that influence classical conditioning outcomes will provide a more comprehensive understanding of learning.

-

Evolutionary perspectives: Investigating the evolutionary origins of cognitive processes involved in classical conditioning, examining how these processes evolved to enhance survival and reproduction, offers valuable insights.

Conclusion

The cognitive view of classical conditioning offers a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of learning compared to the traditional behavioral perspective. By incorporating mental processes such as attention, expectancy, and the formation of internal representations, the cognitive view provides a framework for understanding the active and flexible nature of learning. This understanding has important implications for various fields, from therapy and education to marketing and animal training, highlighting the relevance and continuing importance of this perspective in exploring the complexities of human and animal behavior. Continued research exploring the neural mechanisms, individual differences, and evolutionary underpinnings will further refine our understanding of this fundamental learning process.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Ethics And College Student Life 3rd Edition

Mar 31, 2025

-

Match Each Term With Its Description

Mar 31, 2025

-

Income Smoothing Describes The Concept That

Mar 31, 2025

-

When Can A Notary Submit An Application For Reappointment

Mar 31, 2025

-

A Financial Advisor Schedules An Introductory Meeting

Mar 31, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about According To The Cognitive View Of Classical Conditioning . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.