A Person Pushing A Horizontal Uniformly Loaded

Holbox

Mar 12, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

- A Person Pushing A Horizontal Uniformly Loaded

- Table of Contents

- Analyzing the Physics of Pushing a Horizontally Loaded Object

- Forces Involved in Pushing a Horizontal Object

- 1. The Applied Force (F<sub>a</sub>)

- 2. The Force of Friction (F<sub>f</sub>)

- 3. The Normal Force (F<sub>n</sub>)

- 4. The Weight of the Object (F<sub>g</sub>)

- Conditions for Successful Pushing

- Factors Influencing Ease of Pushing

- 1. The Coefficient of Friction (μ)

- 2. The Weight (or Mass) of the Object (m)

- 3. The Surface Area of Contact

- 4. The Angle of the Applied Force

- 5. Rolling Friction vs. Sliding Friction

- Analyzing the Equilibrium and Motion

- Newton's First Law (Inertia):

- Newton's Second Law (F=ma):

- Practical Applications and Considerations

- Conclusion: Mastering the Physics of Pushing

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

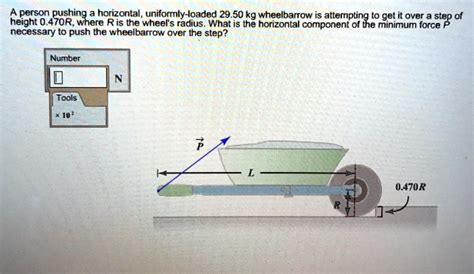

Analyzing the Physics of Pushing a Horizontally Loaded Object

Pushing a uniformly loaded horizontal object, seemingly simple, reveals a fascinating interplay of physics principles. This act, whether it's shifting a heavy crate across a warehouse floor or propelling a laden cart, involves forces, friction, and the crucial concept of equilibrium. Understanding these principles is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications in various fields, from engineering and logistics to ergonomics and even sports. This article delves deep into the physics involved, exploring the forces at play, the conditions for successful pushing, and the factors that influence the ease or difficulty of the task.

Forces Involved in Pushing a Horizontal Object

When you push a horizontal, uniformly loaded object, several forces are at work, interacting to determine the object's motion or lack thereof. These forces include:

1. The Applied Force (F<sub>a</sub>)

This is the force you exert on the object. It's a vector quantity, meaning it has both magnitude (how hard you push) and direction (the direction of your push). Ideally, this force should be applied parallel to the surface the object is resting on for maximum efficiency. Any component of the force directed downwards increases the normal force and thus friction, while any upward component reduces the normal force and friction.

2. The Force of Friction (F<sub>f</sub>)

Friction is the force that opposes motion between two surfaces in contact. In the case of pushing a horizontal object, this is primarily kinetic friction (friction during motion) if the object is already moving and static friction (friction preventing motion) if the object is initially at rest. The force of friction is proportional to the normal force (F<sub>n</sub>) and is governed by the coefficient of friction (μ), which depends on the nature of the surfaces in contact. The equation is:

F<sub>f</sub> = μF<sub>n</sub>

Where:

- F<sub>f</sub> is the force of friction

- μ is the coefficient of friction (μ<sub>k</sub> for kinetic friction, μ<sub>s</sub> for static friction)

- F<sub>n</sub> is the normal force

The coefficient of static friction is generally greater than the coefficient of kinetic friction. This explains why it's often harder to start an object moving than to keep it moving.

3. The Normal Force (F<sub>n</sub>)

The normal force is the force exerted by the surface on the object, perpendicular to the surface. For a horizontal surface, the normal force is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the weight of the object (F<sub>g</sub>), provided there are no other vertical forces acting on the object.

F<sub>n</sub> = F<sub>g</sub> = mg

Where:

- F<sub>n</sub> is the normal force

- F<sub>g</sub> is the force of gravity (weight)

- m is the mass of the object

- g is the acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.8 m/s²)

4. The Weight of the Object (F<sub>g</sub>)

This is the force of gravity acting on the object, pulling it downwards. As mentioned above, on a horizontal surface, this force is balanced by the normal force.

Conditions for Successful Pushing

Successfully pushing a horizontal, uniformly loaded object requires overcoming the force of friction. This means the applied force must be greater than or equal to the force of friction:

F<sub>a</sub> ≥ F<sub>f</sub>

If the object is at rest, you need to overcome static friction. If the object is already in motion, you need to overcome kinetic friction. Since static friction is greater, initiating the push requires a greater force.

Factors Influencing Ease of Pushing

Several factors can significantly influence how easily you can push a horizontal, uniformly loaded object:

1. The Coefficient of Friction (μ)

A lower coefficient of friction implies less resistance to motion. Smooth surfaces generally have lower coefficients of friction than rough surfaces. Using lubricants can reduce the coefficient of friction and make pushing easier.

2. The Weight (or Mass) of the Object (m)

A heavier object has a greater weight, leading to a larger normal force and consequently a larger force of friction. This makes pushing heavier objects significantly more difficult.

3. The Surface Area of Contact

While the force of friction is not directly proportional to the surface area of contact for macroscopic objects, it does play an indirect role. A larger surface area might deform the contacting surfaces more, potentially leading to a greater effective area of contact and an increased friction force. However, this effect is usually negligible compared to the influence of weight and coefficient of friction.

4. The Angle of the Applied Force

As mentioned previously, the most efficient way to push an object is to apply the force parallel to the surface. Applying the force at an angle introduces a vertical component, which can either increase (downward component) or decrease (upward component) the normal force and thus the friction force.

5. Rolling Friction vs. Sliding Friction

If possible, using wheels or rollers drastically reduces friction. Rolling friction is considerably smaller than sliding friction, making it significantly easier to move an object with wheels.

Analyzing the Equilibrium and Motion

To understand the object's motion, we need to consider Newton's first and second laws of motion.

Newton's First Law (Inertia):

An object at rest stays at rest, and an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force. This explains why overcoming static friction is essential to start the object moving.

Newton's Second Law (F=ma):

The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass. The equation is:

F<sub>net</sub> = ma

Where:

- F<sub>net</sub> is the net force acting on the object (the vector sum of all forces)

- m is the mass of the object

- a is the acceleration of the object

When pushing an object, the net force is the difference between the applied force and the force of friction:

F<sub>net</sub> = F<sub>a</sub> - F<sub>f</sub>

If F<sub>a</sub> > F<sub>f</sub>, the object accelerates. If F<sub>a</sub> = F<sub>f</sub>, the object moves at a constant velocity. If F<sub>a</sub> < F<sub>f</sub>, the object decelerates or remains at rest.

Practical Applications and Considerations

The principles discussed above have numerous practical applications:

- Material Handling: In warehouses and factories, understanding friction and the optimal pushing techniques is crucial for efficient and safe material handling.

- Logistics and Transportation: The design of vehicles and transport systems incorporates principles of friction and rolling resistance to minimize energy consumption and maximize efficiency.

- Ergonomics: Designing tasks to minimize the force required for pushing considers factors like object weight, surface friction, and handle design to reduce strain on the worker.

- Sports: Pushing actions in various sports, such as shot-putting or pushing a sled, require careful consideration of force application, friction, and body mechanics.

Conclusion: Mastering the Physics of Pushing

Pushing a seemingly simple act reveals a rich tapestry of physical principles. By understanding the forces involved – the applied force, friction, the normal force, and the object's weight – and the conditions necessary to initiate and maintain motion, we can optimize the process for efficiency and safety. Considering factors like the coefficient of friction, object weight, and surface characteristics allows for a more informed and effective approach to this everyday task. From industrial applications to athletic performance, the principles discussed here offer valuable insights into how to effectively and efficiently move horizontal, uniformly loaded objects. Furthermore, this understanding helps mitigate risk of injury and optimize resource allocation in various fields.

Latest Posts

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Person Pushing A Horizontal Uniformly Loaded . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.